Gobierno de la ciudad de Buenos Aires

Hospital Neuropsiquiátrico

"Dr. José Tiburcio Borda"

Laboratorio de Investigaciones Electroneurobiológicas

y

Revista

Electroneurobiología

ISSN: ONLINE 1850-1826 - PRINT 0328-0446

Christofredo Jakob as a naturalist: The 1923 scientific

voyage aboard

HSDG Cap

Polonio to La Tierra del Fuego - Christofredo Jakob, naturalista:

la travesía científica de 1923 en el Cap Polonio a Tierra del Fuego

Bilingual

edition – Edición bilingüe

by

Lazaros C. Triarhou

Professor of Neuroscience and Chairman of Educational

Policy,

University of Macedonia, Thessalónica 54006, Greece

Contacto / correspondence: triarhou[-at]uom.gr

Electroneurobiología 2007; 15

(2), pp. 61-116; URL <http://electroneubio.secyt.gov.ar/index2.htm>

Copyright © Electroneurobiología, May 2007. This is an Open

Access article: verbatim copying and redistribution of this article are

permitted in all media for any purpose, provided this notice is preserved along

with the article's full citation and URL (above). / Este texto es un artículo

de acceso público; su copia exacta y redistribución por cualquier medio están

permitidas bajo la condición de conservar esta noticia y la referencia completa

a su publicación incluyendo la URL (ver arriba). / Diese Forschungsarbeit ist

öffentlich zugänglich. Die treue Reproduktion und die Verbreitung durch Medien

ist nur unter folgenden Bedingungen gestattet: Wiedergabe dieses Absatzes sowie

Angabe der kompletten Referenz bei Veröffentlichung, inklusive der originalen

Internetadresse (URL, siehe oben). /

. Received:

May 6, 2007 – Accepted: May 26, 2007

Imprimir este archivo NO preserva formatos ni números

de página. Puede obtener un archivo .PDF

(recomendado: 3,5 MB) o .DOC

(3 MB) para leer o imprimir este artículo, desde aquí o de / You can download

a .PDF

(recommended: 3.5 MB) or .DOC

(3 MB) file for reading or printing, either from here or <http://electroneubio.secyt.gov.ar/index2.html

![]()

SUMMARY: A

"Rennaissance amplitude" of scientific interests brands Christfried

Jakob's neurobiological tradition. It requires from researchers to furnish

every acquisition of data – whether observational, experimental or clinical –

with context in other sciences and humanities. The criterion arrived to Jakob

transmitted by his master and friend Adolf von Strümpell, whose father in turn

cultivated it in Dorpat (today Tartu, Estonia), in the line of theoretical

biology and philosophy going from Burdach and von Baer to von Uexküll and

Kalevi Kull. On this criterion, besides his lifelong research pursuits in

comparative and human neuroscience, the multifarious Professor Christofredo

Jakob integrated intellectual interests spanning over a wide spectrum of

fields, and put forward to his disciples a taste for their serious parallel

cultivation. Such fields include general biology, anthropology, paleontology,

biogeography, philosophy, and music. A landmark experience in Jakob's studious

itinerary must have been his 1923 voyage to Tierra del Fuego on board the

steamer Cap Polonio. Jakob presented

a narrative of his impressions at the 12th ordinary session of the

Popular Institute of Conferences, held on Sept. 5, 1924 in Buenos Aires. He studied

the geography, marine biology, fauna and flora of Patagonia, and gathered a

great collection of specimens and documents. The original text of his lecture,

published in the 1926 Proceedings of the Institute, is reproduced herein. Jakob

covers elements from the geography, history of explorations, fauna, and flora

of Tierra del Fuego; he details the stops made and the species observed. Photographic

documentation has been added to help recreate the journey's biological and

historical atmosphere. (English-Spanish edition.)

RESUMEN: La "amplitud

renacentista" de intereses científicos propia de la neurobiología en la

tradición académica de Christofredo Jakob, que exige contextuar en otras

ciencias y humanidades cada adquisición de datos observacionales,

experimentales o clínicos, fuéle transmitida a Jakob por su maestro y amigo

Adolf von Strümpell, cuyo padre la cultivaba en Dorpat (hoy Tartu, Estonia) en

la línea de biología teórica y filosofía que va de Burdach y von Baer a von

Uexküll y Kalevi Kull. Debido a tal

criterio el multifario profesor Jakob, a más de perseguir toda su vida metas de

investigación en neurociencia comparada y humana, también integró y enseñó a

sus discípulos el gusto de cultivar con seriedad profesional intereses intelectuales

que cubrían un amplio espectro de campos disciplinarios, incluyendo biología

general, antropología, paleontología, biogeografía, filosofía y música. Un hito

en sus experiencias ha de haber sido el viaje de 1923 a Tierra del Fuego a

bordo del vapor Cap Polonio. Examinó in situ la geografía, biología marina,

fauna y flora de la Patagonia, y

reunió una gran colección de especímenes

y documentos. Jakob presentó una narrativa de sus impresiones en la duodécima

sesión ordinaria del Instituto Popular de Conferencias en Buenos Aires,

celebrada el cinco de septiembre de 1924. El sucinto texto original de su

exposición, publicado en los Anales

del Instituto en 1926, se reproduce en este trabajo. Jakob tocó allí elementos

de la geografía, historia de las exploraciones, fauna y flora de Tierra del

Fuego, detallando las escalas efectuadas y las especies observadas. Se agrega

documentación fotográfica para contribuir a recrear la atmósfera biológica e

histórica de la jornada.

![]()

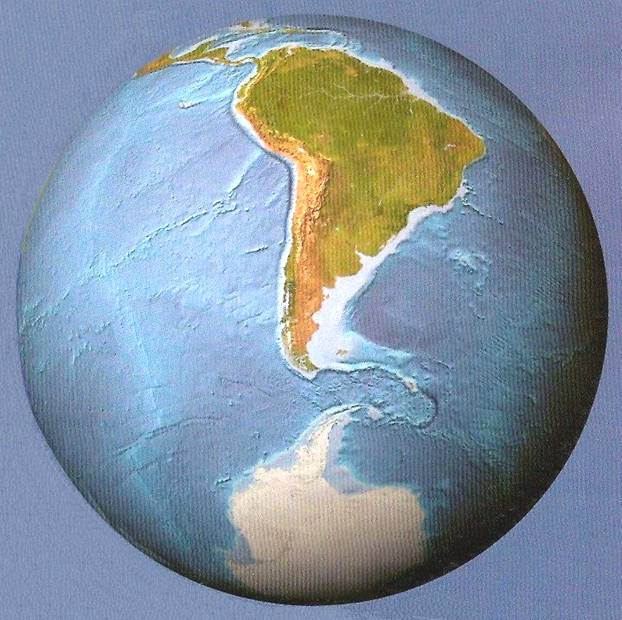

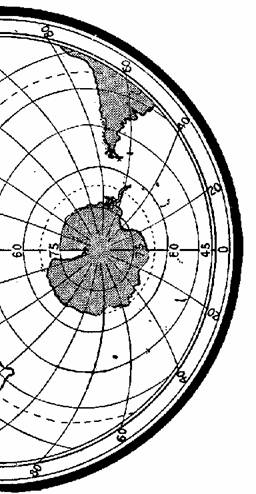

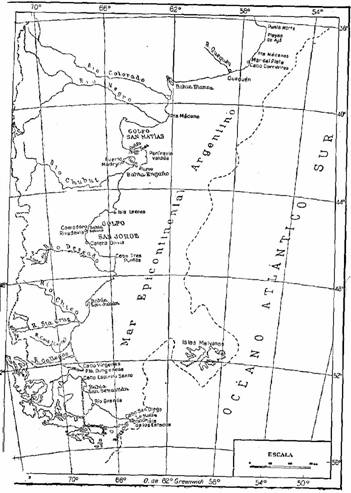

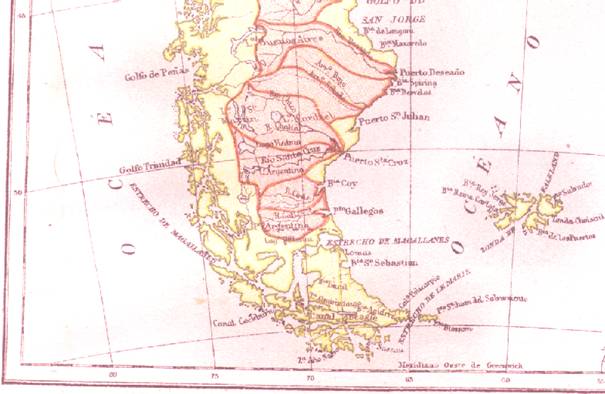

The region / La región

Summer

satellite photos of the whole island. Straits of Magellan above left and the

Beagle Channel below right. Cape Horn is in right bottom corner. The highest

mountain in the area, Mount Darwin, is highlighted near center

Southernmost tip of South America and Artarctica (left);

Tierra del Fuego and Malvinas, Southern Patagonia (right)

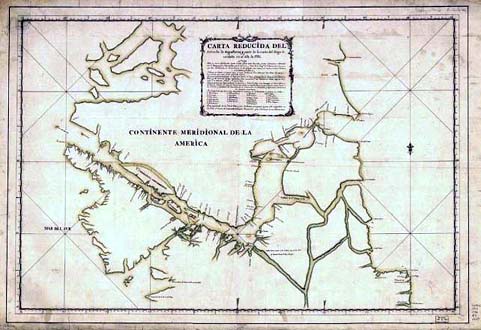

The Strait of Magellan, map by Antonio Córdoba Lazo de la

Vega, 1785/86

(English

section) Introduction

In

the Preface to his Elements of Neurobiology, the ingenious Dr.

Christofredo Jakob notes: ‘On board Cap Polonio, in its cruise to Tierra

del Fuego, January of 1923’ (Jakob, 1923, p. 10). The historic trip of Jakob to

the Land of the Fires (so called for

the natives' bonfires in the coast, seen from the Spanish ships at sea) at the

age of 56 receives mention in the Orlando biography (Orlando, 1966), as well as

in the biosketch by Chichilnisky (2005).

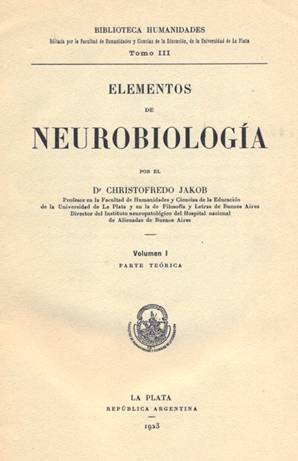

Frontispiece

of Chr. Jakob's classic book published in La Plata (1923) - Cubierta del libro

clásico del Dr. Jakob, Elementos de Neurobiología, publicado en La Plata en 1923.

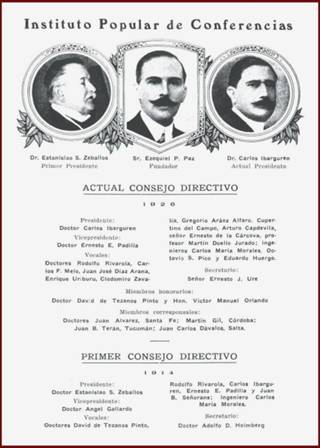

On September 5, 1924, Dr. Jakob gave a lecture

summarizing his impressions from the scientific voyage at the 12th

ordinary session of the Popular Institute of Conferences in Buenos Aires, Dr.

Carlos Ibarguren presiding. That conference appeared in print two years later

in the official proceedings of the Institute (Jakob, 1926). The original text

is reproduced below in its entirety. The graphic documentation has been

inserted to help recreate the historical and naturalistic atmosphere of the

event. Jakob’s extraordinary vitality, the precise movements of his animated figure,

the vivacious and sharp eyes, his pictorial language with the admirable eloquence

of facts that filled his lectures was recalled by Gregorio Bermann (1957).

In his article, Jakob goes over the geography,

exploration history, fauna and flora of the Tierra del Fuego, as well as the

stops made and the species observed. One cannot avoid remembering the historic

voyage of another great naturalist during the previous century, that of the

young Charles Darwin on board the H.M.S. Beagle – which Jakob mentions in his text – that was crucial

for the formulation of the theory of evolution (Darwin, 1839).

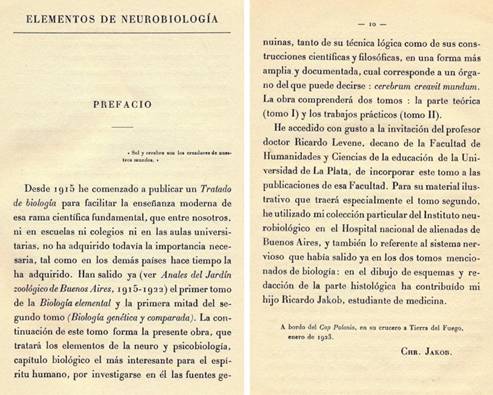

Jakob's Preface, dated in the Cap

Polonio / El prefacio

del Dr. Chr. Jakob para los Elementos de Neurobiología se data en el crucero del Cap Polonio a Tierra del Fuego.

Cap Polonio (weight 20,576 grt, length

202 m) was built as an auxiliary cruiser in 1915 and soon converted to a

passenger ship. Taken over by the British, it was sold in 1921 back to the

original owners, the Hamburg

Süd-Amerikanische Dampfschifffahrts Gesellschaft (H.S.D.G.), and placed on

the Hamburg–El Plata itinerary from

1922 onwards. With the economic crash of 1929, Cap Polonio spent time either cruising or laid up; it was scrapped

in 1935.

Some

details of the voyage were relayed to Chichilnisky (2005) by Jakob’s son Ricardo.

Christofredo Jakob studied the geography and marine biology of the region and

gathered a great collection of materials; seaweed and fish, in particular. He

studied the fauna and flora of Patagonia, and documented everything in fabulous

photographs and glass slides. In southern latitudes he rediscovered paths once

journeyed by the Chilean Indians. Finally Jakob stopped in the Islas Malvinas,

which he crossed in their entirety. After returning to Buenos Aires, he

classified all the gathered material. Years later, Jakob ceded the entire

splendid collection of specimens from the voyage to the Museum of Biology of the

Faculty of Philosophy and Letters (Orlando, 1966). To great dismay, the

collection was lost soon after his death, through carelessness or malevolence

(Chichilnisky, 2005).

First

page of the volume with Jakob's lecture. / Página inicial del volumen del

Instituto Popular de Conferencias que contiene la exposición de Christofredo

Jakob.

Announcement by the Delfino agency of Cap Polonio’s planned voyages to

the Tierra del Fuego.

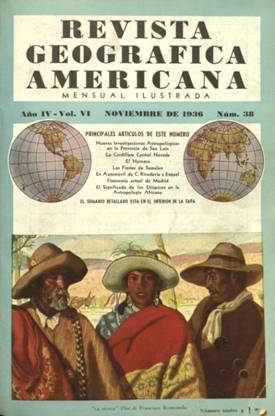

The Naturalist

An ardent

admirer of nature, besides a biologist, philosopher and artist, Jakob journeyed

extensively through unexplored territories of Argentina, Chile, Bolivia and

Perú. He travelled to la Cordillera

Andina (Andean mountain range) and the surrounding regions of Nahuel Huapi,

San Carlos de Bariloche, Puerto Madryn, Puerto Pirámides, Comodoro Rivadavia,

Ushuaia, and Islas Malvinas. Between 1936 and 1940, he published seven articles

in Revista Geográfica Americana, the result of his explorations of the

South American continent (Jakob, 1936a, 1936b, 1937a, 1937b, 1937c, 1939,

1940).

Cover of the issues containing Jakob's communications / Cubiertas de la Revista

Geográfica Americana, donde el Prof. Jakob publicó las impresiones de sus

recorridos biogeográficos.

In the heights of the inhospitable regions, Jakob

enjoyed the spiritual rest offered by the majestic mountain range, at the same

time satisfying over and over his curiosity and thirst for biological knowledge

(Chichilnisky, 2005).

Christofredo Jakob is likely the only neuroscientist in the

world to have a lake named after him: Lago Jakob,

which he explored in 1934, is located 1600 m above sea level, near Bariloche in

the Argentinian Nahuel Huapi region of Western Patagonia (approximately 41° S,

71° W).

The

Revista's List of Collaborators / La

lista de los colaboradores de la Revista, incluyendo el nombre del Dr.

Jakob.

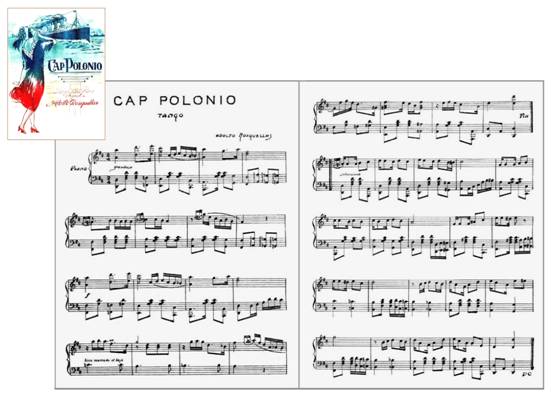

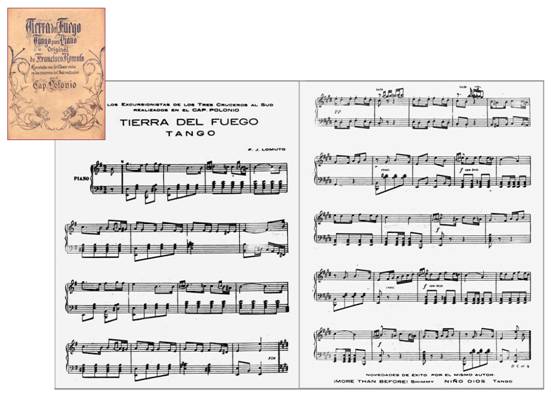

A Musical Note

Music being an integral component of Don Christofredo’s life, one may

mention two apropos compositions: Cap Polonio, tango para piano by

Adolfo Rosquellas (1900–1964), and Tierra del Fuego, tango para piano by

Francisco «Pancho» Lomuto (1893–1950) dedicated to the excursionists of the

three cruises to the South realized in the Cap

Polonio.

Francisco Lomuto Tango Orchestra / La Orquesta Típica de Francisco

Lomuto. Daniel Alvarez y Martin Darré (bandoneón), Leopoldo Schiffrin (violín);

Francisco Lomuto (piano). Fundada en el año 1922, la orquesta tocó a bordo del Cap Polonio en sus cruceros al Sur.

(Crédito: http://www.elportaldeltango.com/orquestas/lomuto.htm).

‘Cap

Polonio.’ Tango para piano compuesto por Adolfo Leopoldo Rosquellas, letra de

Juan Andrés Caruso, grabó Ignacio Corsini. (Partitura:

www.todotango.com).

‘Tierra del Fuego.’ Tango para piano ‘Ejecutado con brillante exito en

los tres cruceros al Sud realizados por el Cap Polonio.’ Performed in the Cap

Polonio's cruises, by/ Compuesto por Francisco Juan Lomuto (misspelt /

deletreado erróneamente ‘Romulo’ en la cubierta), letra del mismo, grabó Carlos

Gardel [http://www.todotango.com.ar/audio/wax/3829.wax]. (Partitura: archivo

privado).

Perhaps one should also

mention that the renowned bandoneonist Manuel Pizarro (1895–1982) was among the performers

on board the Cap Polonio in its

cruise to Canales Fueguinos, along with the members of the Francisco Lomuto Orchestra.

This

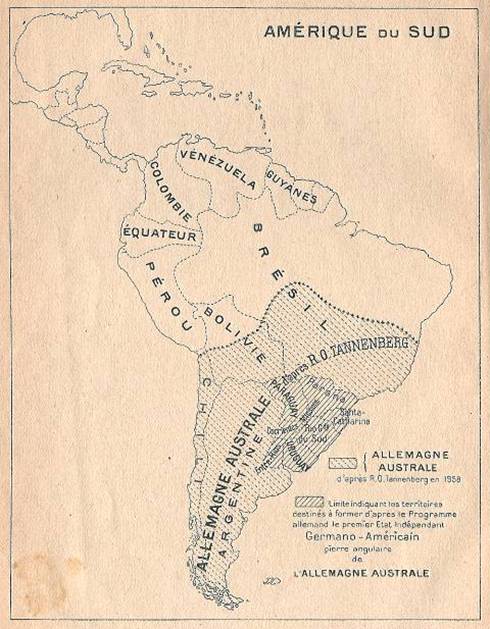

French map of 1918 denounces an assumed German project to shape up for 1958 an

independent German-American state, the nucleus for a future Austral Germany.

Speculations of this sort complicated and attracted extra attention onto the

research by Jakob, who was utterly foreign to political affairs. / Este mapa

francés de 1918 denuncia un supuesto plan alemán de formar para 1958 un estado

independiente germano-americano, núcleo de una futura Alemania Austral.

Especulaciones de esta suerte complicaron y atrajeron atención extra sobre las

investigaciones de Jakob, que fue completamente ajeno a cuestiones políticas.

![]()

(Spanish

section) Introducción

En

el prefacio a sus Elementos de Neurobiología, el infatigable Dr.

Christofredo Jakob anota: ‘A bordo del Cap Polonio, en su crucero a

Tierra del Fuego, enero de 1923’ (Jakob, 1923, p. 10). El histórico viaje de

Jakob a los 56 años a la Tierra de las

Fogatas (así llamada a causa de las hogueras de los nativos en la costa,

avistadas por los sucesivos barcos españoles desde su derrota) recibe mención

en la biografía de Orlando (1966), así como en el esbozo biográfico por

Chichilnisky (2005).

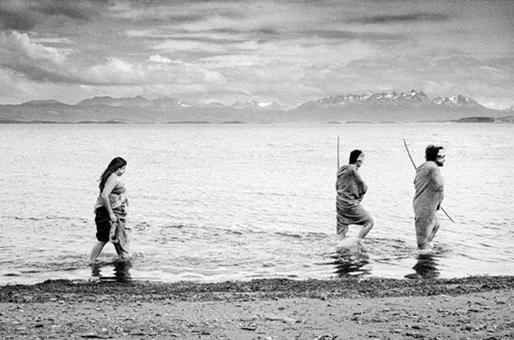

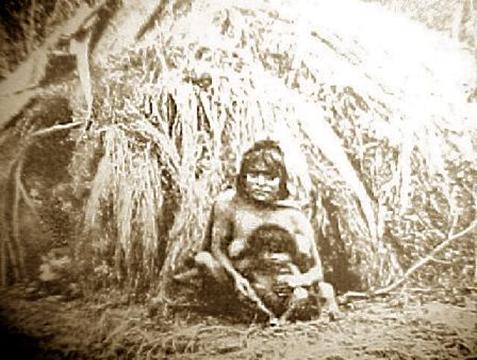

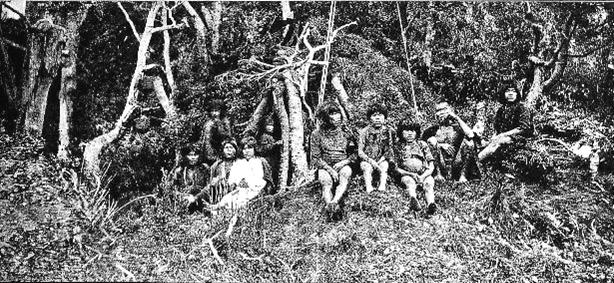

Onas on a tour of a Big

Island of Tierra del Fuego's beach / Onas por la playa de la Isla Grande de

Tierra del Fuego

El cinco de septiembre de

1924 el profesor Jakob brindó una conferencia resumiendo sus impresiones del viaje

científico en la duodécima sesión ordinaria del Instituto Popular de

Conferencias en Buenos Aires, presidida por el Dr. Carlos Ibarguren. La

conferencia salió impresa dos años después, en los Anales del Instituto (Jakob, 1926). El texto original se reproduce

aquí en su integridad. La documentación gráfica ha sido insertada para

contribuir a recrear la atmósfera histórica y naturalística del evento. La extraordinaria

vitalidad de Jakob, los movimientos precisos de su animada figura, los ojos

vivaces e inteligentes, su lenguaje – pictórico por la admirable elocuencia de

los hechos que henchían sus conferencias – fueron recordados por Gregorio

Bermann (1957).

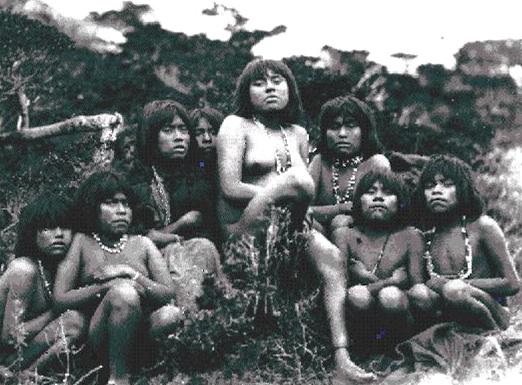

Above: Ona family and Ona hunters

(use Guanaco skin cloaks). Below: a Yagan and Yagan women (use no dress; normal

bodily temperature 38 ºC). All circa 1918, on the Big Island of Tierra del Fuego

En su comunicación, Jakob

tocó la geografía, fauna, flora e historia de la exploración de Tierra del

Fuego, así como las escalas hechas y las especies observadas. Uno no puede

evitar la remembranza, que Jakob también menciona en este texto, del histórico

viaje de otro gran naturalista durante el siglo precedente: la travesía del

joven Carlos Darwin a bordo del H.M.S. Beagle, que resultara crucial para su formulación de la teoría de

la evolución (Darwin, 1839).

El Cap Polonio (tonelaje 20.576, eslora 202 metros) fue construído

como crucero de guerra auxiliar en 1915. Pronto se lo convirtió en barco de

pasajeros: había sido capturado por los ingleses, quienes en 1921 se lo

vendieron a sus originales propietarios, la Hamburg-Süd-Amerikanische

Dampfschifffahrts Gesellschaft (H.S.D.G., Sociedad Hamburguesa-Sudamericana

de Astilleros). Esta lo puso desde 1922 en el itinerario de Hamburgo al Plata.

Tras el derrumbe económico de 1929,

el Cap Polonio navegaba

menos y quedaba mucho en muelle; por

el alto valor de sus elementos, en 1935 resultó redituable desguazarlo.

Cap Polonio – salida de Buenos Aires.

Kolux, Union Postale Universelle.

Algunos

detalles del viaje fueron transmitidos a Chichilnisky (2005) por el hijo de

Jakob, Ricardo. Christofredo Jakob estudió la geografía y biología marina de la

región y reunió una gran colección de materiales: kelp y animales marinos, en particular. Estudió la fauna y flora de

la Patagonia, y documentó todo en fabulosas fotografías y preparaciones de

cortes montados en vidrio. En las latitudes australes redescubrió senderos

otrora hollados por los indios chilenos. Finalmente Jakob hizo escala en las

Islas Malvinas, que atravesó de punta a punta. Tras volver a Buenos Aires,

clasificó todo el material seleccionado. Años después, cedió la espléndida colección completa de especímenes del viaje al

Museo de Biología de la Facultad de Filosofía y Letras de la Universidad de

Buenos Aires (Orlando, 1966). Es motivo de desmayo el hecho de que la colección

se haya perdido a poco de su muerte, por descuido o malevolencia (Chichilnisky,

2005).

El naturalista

Ardiente

admirador de la naturaleza, a más de biólogo, filósofo y artista, Jakob

atravesó extensamente territorios inexplorados de la Argentina, Chile, Bolivia

y Perú. Viajó por la cordillera de los Andes

y regiones circundantes de Nahuel Huapi, San Carlos de Bariloche, Puerto

Madryn, Puerto Pirámides, Comodoro Rivadavia, Ushuaia e Islas Malvinas. Entre

1936 y 1940, publicó siete artículos en la Revista Geográfica Americana,

fruto y resumen de sus exploraciones del continente sudamericano (Jakob, 1936a,

1936b, 1937a, 1937b, 1937c, 1939, 1940).

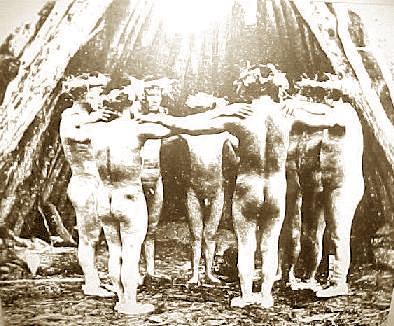

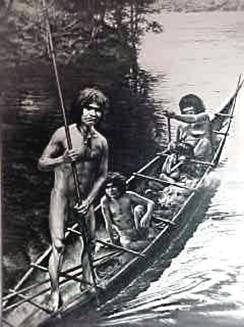

Above: Ona Indian on Tierra del Fuego. Below: Some Yagans performing a ceremony (right) A

Yagan family aboard their beech bark canoe; they carry their fire aboard. The

women did the rowing and the man did the harpooning. Arriba: Onas. Abajo,

izquierda: Yaganes en una ceremonia. Derecha: familia yagana en su canoa de

corteza de ñire, donde llevan el fuego. La mujer rema, el varón arponea.

En

las inhóspitas profundidades de esas regiones gozaba Jakob del solaz espiritual

que ofrecían las majestuosas anfractuosidades, al par que satisfacía una y otra

vez sus expectativas y anhelos de entendimiento biológico (Chichilnisky, 2005).

Christofredo Jakob es

probablemente el único neurocientífico en el mundo que tiene un lago bautizado

con su nombre. El Lago Jakob, que explorara en 1934, se ubica

a 1600 m sobre el nivel del mar, cerca de Bariloche en la región argentina del

Nahuel Huapi, en la Patagonia occidental (aproximadamente 41° S, 71° W).

Lago Jakob

Una nota musical

Habiendo sido la música un componente integral en la

vida de don Christofredo, deben mencionarse dos composiciones muy a propósito: Cap

Polonio, tango para piano por Adolfo Rosquellas (1900–1964), y Tierra

del Fuego, tango para piano por Francisco «Pancho» Lomuto (1893–1950)

dedicados a los excursionistas de los tres cruceros al Sud realizados en el Cap Polonio.

También

debiérase mencionar que el renombrado bandoneonista Manuel Pizarro (1895–1982)

estuvo entre los ejecutantes a bordo del Cap

Polonio en su crucero por los canales fueguinos, junto a los miembros de la

orquesta típica de Francisco Lomuto.

![]()

Instituto Popular de Conferencias

DUODÉCIMA SESIÓN

ORDINARIA DEL 5 DE SEPTIEMBRE DE 1924

Un viaje biológico a Tierra del Fuego

Conferencia del Doctor

Christofredo Jakob

Publicado originalmente en

los Anales del Instituto Popular de

Conferencias,

Decimo Ciclo, Año 1924,

Tomo X, Buenos Aires, 1926, pgs.

155-161.

Entre las diferentes zonas del extenso

territorio de la Argentina y limítrofes de Chile, ocupa la Tierra del Fuego,

con sus 70.000 kilómetros cuadrados, un lugar especial, tanto por su

conformación singular geográfica, que reune en una síntesis superior la

estructura montañosa andina con un complicadísimo sistema de canales oceánicos,

como por la integridad casí absoluta de su fauna y flora autóctonas, las que,

debido a su relativa separación de los centros de acción intensa

agrícola-industrial humana, han podido conservarse en su estado de desarrollo

natural primitivo, sin ser tocadas todavía demasiado por el proceso de

nivelamiento deformante por el hombre, que modifica y explota la superficie

terrestre a sus gustos y necesidades.

Tal combinación de una lito- e hidrósfera

amalgamada en forma grandiosa con una biósfera virginal no contaminada por los

“beneficios de la civilización moderna”, dan a la Tierra del Fuego el carácter

de un “territorio reservado natural”. Y en tal sentido representa el

archipiélago fueguino la perla más pura entre tantas alhajas ya más o menos

“enturbiadas” de las bellezas regionales argentinas, desde los bosques del

Chaco y las cataratas del Iguazú, del Norte, hasta los lagos del Nahuel Huapi y

Esmeralda, del Sur; la que es menester cuidar en una forma más eficiente, para

que en un tiempo cercano no se pierda su brillo natural bajo las manipulaciones,

no siempre limpias, de industriales, banqueros y especuladores desalmados;

porque: “las bellezas regionales pertenecen al pueblo entero, son patrimonio de

la Nación, y así hay que conservarlas como un tesoro inmaculado e inmaculable

argentino”.

Un viaje científico

A esa “joya

geobiológica” os invito a acompañarme, donde una naturaleza primitiva,

deliciosa, mostrará a nuestros ojos sus encantos en paisajes y panoramas desde

lo pintoresco hasta lo imponente y, finalmente, aterrorizante, haciéndonos

olvidar un rato esa cansadora monotonía de la planicie pampeana; donde un aire

limpio y fresco invitará a nuestros pulmones a purificarse de toda esa tierra

pulverizada e infestada, que tragamos forzosamente en las calles de Buenos

Aires (porque nuestra Municipalidad no practica ni obliga debidamente la

antigua regla de higiene elemental: “nunca barrer sin antes regar”); donde el

alma humana gozará de desconocidos placeres espirituales, estéticos, en el

contacto íntimo con una naturaleza prodigiosa en maravillas estupendas de

formas y colores, rodeadas de un silencio casi mágico para un oído maltratado

por la sonoridad antiestética de nuestra vida urbana, y donde la observación

científica encuentra entre los hombres autóctonos, como en animales y plantas de

tierra y mar, los ejemplos más interesantes para el estudio de la organización

vital, riquísima en formas, que allí ha brotado, adaptándose a las condiciones

especiales que clima, suelo y océano en tan singular reunión ofrecen a sus

huéspedes.

Postcard, 1905 / Tarjeta postal de 1905: Lago Nahuel Huapi con la Isla

Victoria, Neuquen, Rep. Argentina.

Editor: R. Rosauer, Buenos Aires. Neg. Sr. Otto Mühlenfordt.

A todo

eso se agrega un atractivo sentimental más: el archipiélago fueguino ha

encerrado siempre para todos sus visitantes, y así lo expresan hasta hoy día,

un algo de misterioso. Todavía persiste ese carácter de “tierra incógnita” en

muchos sentidos, y nos atrae la sensación vaga de que nos esperarán sorpresas,

quizás no sospechadas, allí, donde tierra, hielo, agua y aire, tantos elementos

antárticos en mística combinación, nos impresionarán. Adelante, entonces; ya

estamos ansiosos de experimentar algo sensacional, nuevo en este viejo y moroso

planeta.

Tierra

del Fuego representa, geográficamente, la terminación sur de la cordillera

andina y sus mesetas adyacentes, que allí se precipitaron en el abismo interoceánico.

Quizás tal cataclismo geológico esté relacionado con ese viejo continente

austral, que en períodos geológicos primordiales reunió a la América del Sur,

separada entonces todavía por largas épocas de la del Norte, con la región de

la actual Nueva Zelandia, con la cual y con Australia existe, según notables

hechos paleontológicos, un parentesco ancestral geobiológico mucho más íntimo

de lo que la actual posición geográfica lo haría suponer. Quizás en esas profundidades

oceánicas que rodean el archipiélago fueguino encierra la Tierra, en sus

entrañas sepultadas hoy día, los residuos de esa vida primordial austral y

antártica, misteriosa, formando el cementerio de un colosal continente del

pasado terrestre – del cual, por el otro lado, debe descender en parte la

autóctona vieja fauna y flora de hoy, si bien será mezclada con la sangre y

savia de la que más tarde inmigró de otras zonas; porque, invariablemente,

observamos en la paleobiología que la combinación fértil del elemento autóctono

con lo peregrino representa la fuente de nuevas especies ascendentes, puesto

que el progreso orgánico natural es hijo del cruzamiento de razas sanas y

variadas, tanto en el hombre como en animales y plantas, y pese eso a todos los

“chauvinistas sistematizados”.

Expediciones históricas

Ahora un poco

de orientación histórica respecto a las expediciones exploradoras más

importantes, que nos han allanado y preparado el paso hacia Tierra del Fuego.

El 21 de

octubre de 1520 descubre Magallanes esa tierra, y lo primero que exclama, es:

“no hay país más sano que ese” (textual). Su estudio hidro-orográfico lo

emprenden Drake (1578), Weddell, Cavendish, Bougainville y otros en los siglos

siguientes. Especialmente laborioso ha sido el siglo pasado, que completa los

fundamentos geo-orográficos, y echa las bases para su estudio biológico.

Numerosas expediciones científicas antárticas juntaban valioso material para la

primera fase de la biología, la descripción y sistematización de sus formas

zoológicas y botánicas; aludimos a la expedición de la Uranie y la Physicienne

(1819/20), los dos viajes del Beagle

(capitanes King, 1826/30, y Fitz Roy, 1831/36); en ese último viaje se encontró

a bordo del Beagle el joven Ch.

Darwin, el célebre biólogo inglés, que concebía durante ese viaje sus teorías

de la descendencia orgánica natural.

Fruto de la

expedición antártica del Erebus y el Terror (capitán Ross) fue la publicación

de la primera botánica por Hooker, Flora

Antártica (1842). Al lado de los ingleses aparecen ahora franceses,

alemanes, suecos, belgas, italianos; y, finalmente, también los hijos del país.

Recordamos la

expedición del Nassau (1868/70), de

la Gazelle (1854), de la Romanche (1882/3), de Nordenskjöld

(1895), de Michaelsen de Hamburgo (1892), y de Charcot (1908).

En 1881 se

organizó una expedición argentina bajo la dirección del explorador italiano

Bove, inspirado por el doctor Estanislao S. Zeballos, presidente de la Sociedad

Geográfica Argentina; y su fruto era entre documentos científicos de valor,

como el informe del botánico Spegazzini, etcétera; también la colocación de

faros en esa ruta, hasta entonces sumamente peligrosa, como lo comprueban

numerosos naufragios de buques expedicionarios. Tal iniciativa se debe al entonces

ministro doctor Bernardo de Irigoyen, y hago un voto de aplauso póstumo para la

actuación tanto científica como patriótica de ambos próceres nacionales, porque

gracias a ellos navegan hoy tranquilamente los buques hacia el Sur.

Otra expedición

argentina patrocinada por el museo de La Plata iba en 1896 con el doctor

Lahille para estudiar la fauna marítima, y hace pocos años envió el ministerio

de Agricultura otra misión con los doctores Doello Jurado y Pastor… aparte de

otros aislados viajes de geólogos, antropólogos y naturalistas que penetraban

hacia el interior de la Tierra del Fuego como Bove y Noguera, ya en 1884, Ramón

Lista de la Argentina, J. Popper, y Schelze de Chile, en 1886.

Some of the explorations were carried out in full

despise toward the aborigins. Under Julius Popper's (left; standing up in the

other images) feet, who ex profeso

staged these 1886 photos as a trophy, the corpse of one of the Onas gunned down

/ Algunas de estas exploraciones se llevaron a cabo en total desprecio al

nativo. Bajo los pies de Julio Popper (izq.; erguido en las otras dos

imágenes), que en 1886 montó ex profeso

estas fotos-trofeo, el cadáver de uno de los onas asesinados.

Las colecciones

de tal material geológico, mineralógico, zoológico, botánico y antropológico

llenan numerosos tomos de revistas y monografías científicas, publicadas en

inglés, francés, alemán y castellano, y muchísimo está todavía por aparecer.

La naturaleza

argentina es tan rica en material de enseñanza biológica que podría renunciarse

a todo lo ajeno sin perder la posibilidad de un estudio biológico completo en

cualesquiera de las direcciones de esa gran ciencia fundamental. Querríamos,

después, en especial hacer estudios sobre ciertos problemas de la reproducción

de algas marinas.

Lo que hasta

ahora se ha hecho es sólo el primer paso para penetrar en los complejos

problemas biológicos fueguinos: se ha elaborado una clasificación sumaria de

animales y plantas de esas regiones. El segundo es el estudio de su

organización superior, su fisiología comparativa; después, necesitaremos conocer

las condiciones de su desarrollo embrionario, la protección de la cría, sus medios de nutrición, de defensa; y, finalmente, sus agrupaciones biosociales, sus migraciones,

etcétera. Todo eso está por hacerse.

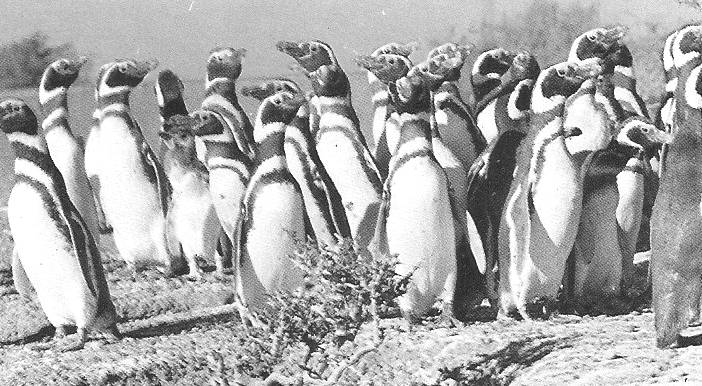

Above: three

images of Punta Tombo penguin camp, South to Valdés Península, Chubut / Arriba:

tres imágenes de la pingüinera de Punta Tombo, al sur de la Península de

Valdés, Chubut. Below: German-made Fauck perforation machine for oil

extraction, at work in Comodoro Rivadavia around 1915 / Abajo: perforadora

alemana Fauck empleada para extracción de petróleo en Comodoro Rivadavia,

Chubut, alrededor de 1915.

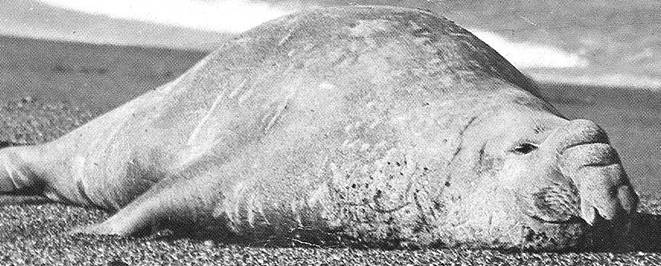

Three above:

marine elephants. Below: orca at the beach, playing whale, sunbathing sea

wolves (three images), and penguins of Magellan.

Fauna fueguina

Sabemos, por de

pronto, que la fauna fueguina es pobre en tierra, abundantísima en cambio en el

aire y, sobre todo, en el agua. Gozando de un clima algo mejor que el sur de la

Patagonia, pues la influencia oceánica se hace sentir, el invierno es allí más

tolerable. Las temperaturas mínimas en los canales pueden llegar en invierno a

10 grados bajo cero; pero el promedio es de 2 a 3 grados sobre cero, siendo la

media annual de 6 a 7 grados; algo más frío en el Norte, donde los vientos

pueden penetrar con más furor. En las bahías del Sur existe en verano una

temperatura muy agradable, de 15 a 20 grados. Lluvias y nieve, hay en

abundancia, siendo el Norte más seco; el clima en general es más húmedo en el

Sur, pero muy variable, debido al cambio rápido de los vientos. Si bien las

condiciones terrestres no son demasiado agradables – por su inconstancia – para

los seres que viven en tierra, en cambio son mucho más tolerables y uniformes

en el agua, y así se explica el fenómeno biológico de su distribución

cuantitativa en favor del agua.

Entre la fauna

terrestre de mamíferos está el guanaco (el reno del indio ona), una especie de

perro y dos de zorros, una liebre de piel muy apreciada (equivocadamente

llamada nutria, pero es piscívora), numerosos pequeños roedores, liebres y

ratones. Faltan por completo desdentados y felinos. Enfrente de esa pobreza hay

muchos mamíferos marinos: focas de gran variedad, lobos y leones marinos,

delfines, ballenas de numerosas especies pueblan los canales y bahías. Pero

varias ya sufren persecuciones fatales.

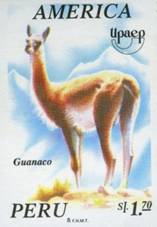

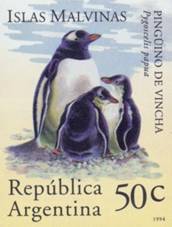

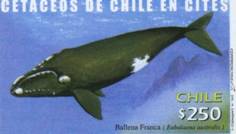

Guanaco, penguins, whale, from South America. Next pages:

seawolves, kaikens, penguins of Magellan, cormorans/ Fauna del continente

suramericano: guanaco, pingüinos, ballena; pág. sig., lobos marinos, pingüinos,

cormoranes..

Penguin of Magellan, grayhead kaiken / Pingüino de Magallanes, kaikén

de cabeza gris.

Pharo / Faro Les Éclaiseurs (Beagle Channel)

Aves existen en

enormes cantidades, verdaderas nubes de cormoranes, gaviotas, albatros,

avutardas, gansos, patos, etcétera, que viven del mar; y otras clases de

pájaros terrestres. Reptiles y anfibios escasean. En cambio, hay multitud de

peces de todas clases, en agua salada y dulce. Insectos, pocos (hay un tábano

molesto y también mosquitos) – pero moluscos marinos, crustáceos, equinodermos,

celenterados en masas fabulosas.

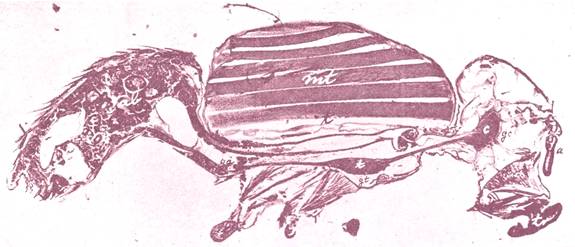

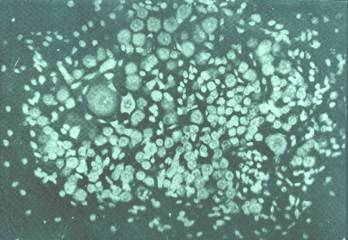

Domestic fly,

infrequent in the region; medial from a series of sagital slices. / Mosca

doméstica, infrecuente en la zona; medial de una serie de cortes sagitales. c, t, ab: encephalic, thoracic, abdominal

ganglia. Jakob's preparation.

Flora fueguina

También la vida

vegetal gravita hacia el agua. Los grandes bosques viven al pie de los

ventisqueros y de sus efluvios, y en el fondo de los canales y bahías se

extiende el reino de las algas, en una variación como en ninguna otra zona de

Sud América. Cerca de la costa parece el fondo marino un jardín, atestado de

flora de todos colores hasta donde penetra la luz solar, y en las aguas

saladas, que son cristalinas, se desarrolla ese reino de las algas con ejemplares

magníficos de muchos metros de largo. La Macrocystis

pyrifera tiene ejemplares de cien metros de largo, que flotan en las aguas

formando islotes peligrosos hasta para naves mayores; otras formas, de colores

que varían del moreno al amarillo, violeta y rojizo, son las Lessonia, Delesseria, Laminaria, Ulva, florídeas; y mayor todavía es la

enormidad de algas pequeñas hasta microscópicas, clorofíceas, y cianofíceas

[que no se clasifican más como algas]. Una alga, la Chlamydomonas, produce allí el fenómeno de la nieve roja, y otra combinación

la de la nieve verde. Conócense más de 500 especies diferentes y mucho más

falta todavía a la clasificación. En tierra nos impresionaron los bosques de

hayas (Nothofagus antarctica, ñire),

con tres variedades, una de hojas perennes, otras caducas llamadas allí roble y

coligüe; bosques, que hasta 300 y 400 metros de altura ascienden en las

montañas hasta que formas enanas, musgos, y líquenes los continúan a mayores

alturas, hasta 1.500 metros, donde la furia de los temporales ya no deja crecer

ni planta alta ni baja. El bosque es de una densidad casi tropical en las

bahías saturadas de agua y defendidas contra los fríos excesivos.

A bordo del Cap Polonio

Antes de todo necesitamos arreglar las maletas biológicas: tarros,

frascos, latas, líquidos de conservación, fenol, redes, aparatos de pesca,

palas; la instalación microscópica de viaje es indispensable. Y ahora, a la

expedición. ¡Adiós, Buenos Aires! ¡Bienvenida, Tierra del Fuego! Salimos a

bordo del Cap Polonio (¡han cambiado

los tiempos!), y llegamos a Puerto Madryn. Observamos las loberías ([lobos] de

un pelo) en Pirámides y pescamos en el golfo, recogiendo moluscos, crustáceos,

isópodos, y además en abundancia pejerreyes chicos, que allí se crían. Llegamos

a Comodoro Rivadavia; visitamos los campos de explotación petrolífera, aunque

más nos interesa la flora xerófila de esas tierras áridas, y su fauna marina;

la bajamar nos proporciona equinodermos: estrellas de mar; anémonas variadas

marinas, anélidos, etcétera.

Postcard from 1923/Tarjeta postal de 1923: Dreischrauben-Schnelldampfer „Cap Polonio“ bei dem Feuerlandinseln.

Hintze

& Wulf, Hamburg 1 / Claus Bergen, München.

Cubierta de paseo

/Promenade-Deck of Cap Polonio.

Offizielle Postkarte des Deutschen Museums München (echte Fotografie /genuine

photo). J. Lindauersche Universitätsbuchhandlung (Schöpping), Kaufingerstr. 29,

München.

Dining room /comedor/ Speisesaal

1. Klasse des Dreischrauben-Postdampfers Cap Polonio. C M & S, Hamburg.

Pero hay que

trabajar, trepando de roca en roca: “con el sudor de tu cara ganarás también el

pan” marino.

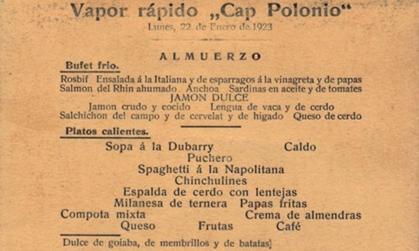

Carte du jour, Jan. 22, 1923 / El menú a

bordo del lunes 22 de enero de 1923.

Seguimos viaje

y entramos en el canal de Magallanes, de costas bajas, poco impresionante;

llegamos por las angosturas y senos conocidos a Punta Arenas, considerable

ciudad chilena, con un museo marino, interesante colección de algas, que es el

trabajo de los padres salesianos. En una excursión a la costa coleccionamos los

primeros ejemplares de algas florídeas, que nos parecen algo del otro mundo.

Juntamos todo lo que podemos, para tirar la mayor parte al otro día en cambio

de ejemplares mejores.

En el puerto

Harberton visitamos nuevamente las costas y sus bosques. Hallamos un esqueleto

de ballena, huevos y nidos de aves, enormes ejemplares de algas, crustáceos,

hidromedusas y pólipos de color, briozoarios de nuevas especies.

Boarding passengers in the longboat / Pasaje en el bote de embarque,

en las aguas del Sur.

El viaje sigue

ahora al Sur; cruzamos la isla Hoste con sus formas peninsulares poliposas,

fondeamos en la bahía Orange; ya terminan los bosques, sólo algunos musgos y

algas vegetan sobre rocas ennegrecidas, barridas por vientos y olas. Al otro

día pasamos el punto más central, el terrible cabo de Hornos, con un océano

tranquilo y liso como un espejo; y tomando ahora rumbo hacia el Norte, cruzamos

la Isla de los Estados con sus montañas horrorosamente fracturadas, así como la

Isla del Año Nuevo, regiones habitadas por millones de aves, colonias de

pingüinos y gaviotas, que atraviesan en masa la atmósfera, mientras que en los

mares viajan los delfines y ballenas en todas direcciones. Ya satisfechos,

llegamos a las islas Malvinas: a casa.

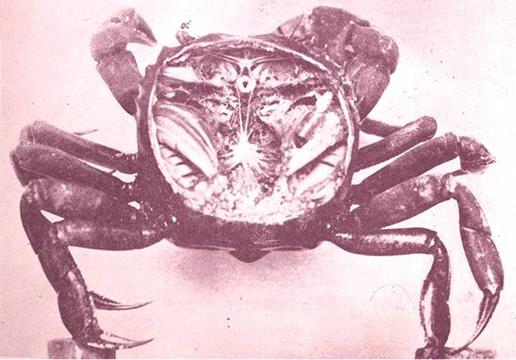

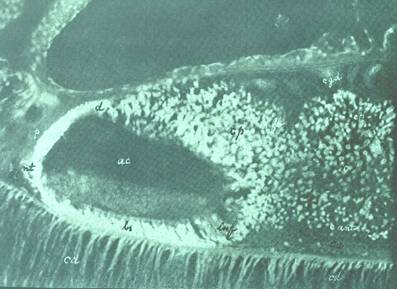

Crustacean from

the Río de la Plata, showing encephaloid ganglion (to which the antenary

anterior, optic, and lateral oculomotor nerves enter), abdominal (celiac

plexus) ganglia, and intercalary (conective) and peripheral nerve systems.

Jakob's preparation.

Conclusión

Pero ahora

empieza el verdadero trabajo; hay que seleccionar, revisar, ordenar las

colecciones; clasificar con el microscopio las especies y variedades, labor

muchas veces imposible por falta de datos.

Cut through the

cerebroid ganglion of the above: neuropil (np);

neurocytomas (nc): tacto-olfactory,

optical (lateral), tacto-motor and gustative (posterior) ones, plus central

commisure. Jakob's preparation

Terminamos

nuestra excursión insistiendo de nuevo en la necesidad urgente de que las altas

autoridades velen por la integridad de las bellezas y productos de la

naturaleza del Norte y Sur. Y al mismo tiempo, deben ellas contribuir más

intensamente para que los estudiosos del país – y hay muchos – tengan posibilidad

de conocerlas y de aprovechar sus enseñanzas en bien de la juventud argentina,

porque solo conociendo su país y sus formas vitales se despierta el verdadero

amor por él. El patriotismo debe constar en hechos y no en frases. La forma más

eficiente para conseguir eso sería la organización de un instituto biológico

nacional con museo biológico y estaciones anexas para trabajos prácticos y

elaboración de colecciones en las zonas más importantes del Norte y Sur argentino,

y la estación biológica futura de Ushuaia estará entre las primeras. Ojalá que

se encuentre un sucesor de Bernardo de Irigoyen que inaugure ese faro científico

en Tierra del Fuego.

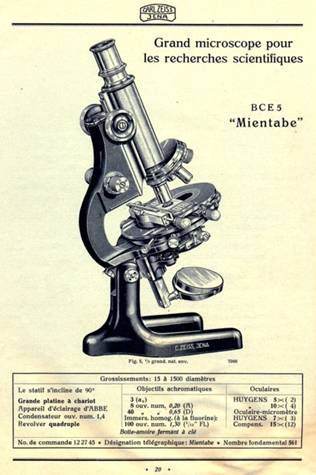

Above/Arriba: ‘Microscopes et appareils auxiliaires.’ Extrait du catalogue français

de 1924; Carl Zeiss, Jena. One instrument of the left model

is still (2007) in continuous use in Jakob's laboratory, Hosp. Borda / Un

instrumento del modelo de la izquierda se halla en buen uso en el laboratorio

de Jakob, Hosp. Borda (2007).

Histological slice of the central optic neurocytoma

in the cerebroid ganglion of the above crustacean. Large ganglion cells

(motor), middle sized and small cells (intercalary and sensitive?) with nuclei

and"cromatina"; interstitial (fusiform) cells, and neuroglia. Jakob's

preparation.

Cerebroid ganglion of a mollusk (Limax, "babosa"): four ganglia

surround the oesophagus (es), each

with neuropil (np) and cytoma (nc). Below, small squid: brain

histotopography, with central neuropil (npc)

and neurocytomas (nc). All

preparations by Jakob.

Amphioxus archiencephalic cerebral vesicle, 500x. o, pigment (rudimentary retina in lamina

terminalis); nt, nervus terminalis

entrance (olf.); basal and dorsal ependym (ns,

d) infundibular area (inf) or

hypophysary fovea, and bulbospinal intercalar cells. Below: Median, somehow lateral, sagital slice

of the amphioxus head: vc, cerebral

vesicle or ampoule, cg giant dorsal

cells, nt, nervus terminalis

entrance.

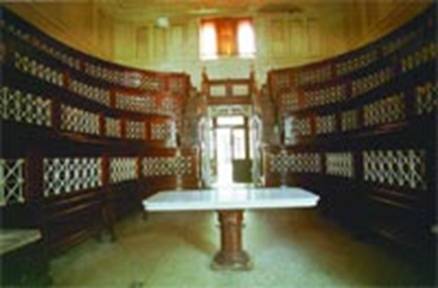

After the cruise, homework: synthesis in comparative

and human neuroanatomy, and classroom work in the laboratory (Hosp. Moyano,

page 91)./ Tras el crucero, los deberes: producir síntesis en neuroanatomía

comparada y humana, enseñar (aula del otro laboratorio, en el Hospital Moyano,

página subsiguiente).

Larval

tunicate: single archiencephalic vesicle (acf), neuropore (po), dorsal chord (cc).

Below, two young sharks show (lateral) the sensory series (ol, nol, olfactory; oc, lc,

ocular; lb, labyrinth) and (median) the

three vesicles. Striatum, str. Lobes:

olfactory, lo; superior, ls. Cerebellum, cb.

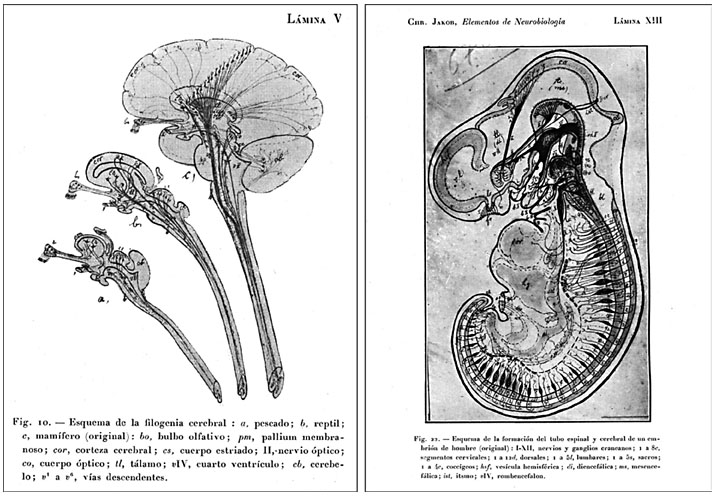

Chr. Jakob's original illustrations (above) to

demonstrate brain's phylogeny (left) and the human neural tube's ontogeny

(right); below, main classroom expressly built in the laboratory at the

Hospital Moyano as a replica of the main classroom at Jakob's University of

origin in Erlangen, later bombed down in WWII. / Ilustraciones de Chr. Jakob

para demostrar la filogenia cerebral (izq.) y la ontogenia del tubo neural

(der,); y aula magna (abajo) construida expresamente para su uso con el

laboratorio del Hospital Moyano; reproduce el aula magna de la universidad de

origen de Jakob, Erlangen, que luego fuera destruida en los bombardeos de la

segunda guerra mundial.

Postcard,

1920 / Tarjeta postal de 1920: Hamburg

Südamerikanische Dampschifffahrts-Gesellschaft

„Cap Polonio“ bei Fernando Noronha. Hintzer & Wulf, Hamburg 1.

![]()

Public Institute of Conferences,

Buenos Aires

Twelfth Regular Session, September 5, 1924

A biological voyage to Tierra del Fuego

A

Conference by Doctor

Christofredo Jakob

Originally published in Annals of the Public Institute of Conferences, Tenth

Cycle – Year 1924, Buenos Aires,

1926, vol. 10, pp. 155–161 (Jakob, 1926). First English translation.

Between the

different zones of the extensive bordering territory of Argentina and Chile,

the Tierra del Fuego – with its 70,000 square kilometers – occupies a special

place. So this is, as much by its singular geographic conformation, which in a

superior synthesis reunites the Andean mountainous structure with a most

complicated system of oceanic channels, as by the almost unreduced wholeness of

its native fauna and flora, which, due to their relative distance from the centers

of intense agricultural-industrial human action, have been able to keep

themselves in their primitive state of natural development, not yet excessively

touched by the process of deforming leveling by humans, who modify the terrestrial

surface and exploit it to their tastes and needs.

Such a

combination, of a lithosphere and a hydrosphere amalgamated in magnificent form

with a virginal biosphere uncontaminated by the “benefits of modern

civilization”, lends to the Tierra del Fuego the character of a “natural

reserve territory”. In this sense, the Fueguean archipelago represents the purest

pearl among the many jewels – more or less “clouded” already – of Argentine

regional beauties, from the Chaco forests and the falls of Iguazú in the North

to the Nahuel Huapi and Esmeralda lakes in the South; a pearl, that one, that

is necessary to care of in a more efficient form, so that in the near future

its natural brightness is not lost under the manipulations, not always clean,

of industrialists, heartless bankers, and speculators. That is so, indeed, because

“regional beauties belong to all the people, they are a Nation's patrimony, and

it is therefore necessary to preserve them as an immaculate, undefilable Argentinian

treasure”.

A

Scientific Voyage

To that

“geobiological jewel” I invite to you to accompany me, whereto a primitive,

delicious nature will put before our amazed eyes all its enchantments,

landscapes and panoramas – from the colorful through the imposing to the

frightening – making us for a while to forget the tiring monotony of the

Pampas' plain. A “geobiological jewel”, that one, whose clean, fresh air

invites our lungs to cast off all that infested dust, blown about, that we

inevitably swallow in the streets of Buenos Aires – because our Municipality

does not properly practice nor reinforces the old rule of elementary hygiene,

“never to sweep without watering before”. A “geobiological jewel”, where the

human soul, surrounded by a silence almost magic for our eardrums mistreated by

the ugly loudness of urban life, enjoys undreamt spiritual and aesthetic

pleasures, in the intimate contact with a nature unsparing in wonderful marvels

of form and colors, where the scientific observation finds – in the native

people, as well as in the animals and plants on earth and at sea – the most

interesting examples to study the vital organization, so rich in forms, that

there has blossomed forth, by adapting itself to the special conditions that

the singular conglobation of climate, soil, and sea offers up to its guests.

Previous page and this, above: a Yagan

house; Yagan girls and boys. Hereinabove, a group of young Yagans

To all that

sentimental attractive, one more is added: for all its visitors – and so they

say it, until nowadays – the Fueguean archipelago has always enclosed something

of mysterious. In many senses, that “incognite land” character still persists.

And it attracts the vague sensation that surprises will wait for to us, perhaps

unimagined, there where earth, ice, water and air – so many Antarctic elements

in mystical combination – will impress us. Let's go, then; we are already

anxious to live through something new, cause of intense interest, curiosity, or

emotion in this old glowering planet.

Laminaria digitata washed up on the shore - fronds over 2 m long each / Laminarias de

más de 2 m echadas a la playa.

Tierra del Fuego

represents, geographically, the Southern ending of the Andean mountain range

and its adjacent plateaus, which in that location hurried into the interoceanic

abyss. Maybe this geological cataclysm is related to the old austral continent

that, in past geologic periods, reunited the Southern America, then still and

for long time separated of the North one, with the region of the present New

Zealand, with which and with Australia, according to notable paleontological

data, an ancestral geobiological kinship exists: one, far more intimate than

what the present geographic position would make us suppose. Maybe in the

oceanic depths that surround the Fueguean

archipelago does the Earth lock up, in its nowadays

buried entrails, the remains of that

mysterious, austral and antarctic primordial life, forming the cemetery of a colossal continent of the

terrestrial past, from which, by the other branch, it must partly descend the

old native fauna and flora of today, though surely mixed with the blood and sap

of later immigrants from other zones, because in paleobiology it is invariably

observed that the fertile combination of the native element with the travelling

one represents the source of new ascending species – since the natural organic

progress is a child of the crossover of healthy and varied lineages, as much in

human as in animals and plants, despite all the protests by

“systematized Chauvinists”.

Historical

Expeditions

Now a bit of historical orientation, as

regards the most important exploring expeditions that made even and prepared

for us the travel toward Tierra del Fuego.

On October 21, 1520, Magellan discovers that

land, and the first that he says was: “There is no other country healthier than

this!”. The hydrographic-orographic study was undertaken by Drake (1578), Weddell,

Cavendish, Bougainville, and others in the following centuries. The last century

has been specially efficient. It completed the geo-orographic groundwork, and

threw the bases for biological studies. Numerous Antarctic scientific

expeditions collected valuable materials for the first phase of biological

work, namely the description and systematization of zoological and botanical

forms. We point to the expedition of the Uranie

and the Physicienne (1819/20) and

both trips of the Beagle under Captains

King, 1826/30, and Fitz Roy, 1831/36. In the latter trip, aboard the Beagle was the young Ch. Darwin, the

celebrated English biologist, who during that trip conceived his theories of

the natural organic descent.

A fruit of the Antarctic expedition of the Erebus and Terror (Captain Ross) was the publication of the first botany by

Hooker, Flora Antarctica (1842). Next

to the English appeared the French, then the German, Swedish, Belgian, Italian,

and finally the sons of the country as well.

We remember the expeditions of the Nassau (1868/70), of the Gazelle (1854), of the Romanche (1882/3), of Nordenskjöld

(1895), of Michaelsen of Hamburg (1892), and of Charcot (1908).

In 1881 an Argentine expedition was organized

under the direction of Italian explorer Bove, inspired by doctor Estanislao S.

Zeballos, president of the Geographic Society of Argentina, that bore fruit of

value, such as scientific documents, like the report of the botanist

Spegazzini, etc., as well as the positioning of lighthouses in that route,

extremely dangerous until then as the numerous shipwrecks of expeditionary

ships make manifest. This initiative is owed to the then minister, doctor

Bernardo de Irigoyen; and I request a posthumous applause for the scientific

and patriotic deeds accomplished by these two national champions, because it is

thanks to them that today ships sail at ease southwards.

Another Argentine expedition, sponsored by the

Museum of La Plata, went in 1896 with doctor Lahille to study the marine fauna;

and few years ago the ministry of Agriculture sent another mission with the doctors

Doello Jurado and Pastor, not to mention other isolated trips by geologists,

anthropologists, and naturalists who penetrated into the midland of Tierra del

Fuego, like Bove y Noguera, in 1884, Ramón Lista of Argentina, J. Popper, and

Schelze of Chile, in 1886.

The collections of geological, mineralogical,

zoological, botanical, and anthropological material fill many volumes of

scientific journals and monographs, in English, French, German and Spanish, and

very many ones are still about to appear.

Nature in Argentina is so rich in materials

for biological research, that one could give up all the other peoples’ material

without losing the possibility of a complete biological study in any of the

leads of that great fundamental science. We'd later like, in special, to carry

out studies on some problems concerning the reproduction of marine algae.

Lichen hung

from a ñire (Nothofagus antarctica) /

Liquenes colgando de un ñire / (right)

Kelp forest.

What has been until now made for penetrating

into the complex Fueguean biological issues is only the first step: a summary

classification has been elaborated, of animal and plants of these regions. The

second step is the study of their higher organization, their comparative

physiology. Later we will need to know the conditions of their embryonic

development, the protection of the young, their means of nutrition and defense,

and finally their biosocial grouping, their migrations, etc. All that is still

to be made.

Fueguean fauna

A gnat's near-medial sagital section / Sección sagital casi mediana de un mosquito: cb, cerebroid ganglion; est, gnathal appendages: proboscis (the greatly elongated sheathlike labium and enclosed fascicle), and the maxillary palpi.

We know, in the first place, that the Fueguean fauna

is poor on land, most abundant yet at air and, mainly, in water. Enjoying a

climate somewhat milder than the South of the Patagonia, as in Tierra del Fuego

the oceanic influence makes itself to feel, the winter there is more tolerable.

The minimum temperatures in the channels can reach 10 °C below zero in winter,

but the average is of 2 °C to 3 °C above zero, the average annual being some 6

°C to 7 °C; somewhat colder is the North, where the winds may penetrate with

more strength. In the bays of the South, there is in summer a very pleasant

temperature, 15 °C to 20° C. Rains and snow are abundant, being the North the

drier; the climate is in general more humid to the South, but very variable due

to the fast change of winds. Although for the creatures living on land the

weather conditions are not too pleasant – by their unevenness – they however

are far more tolerable and uniform in water. This explains the biological

phenomenon of their more abundant quantitative distribution, in favor of the

water.

Colehual, bush of entangled colihues/ matorral de

colihues enmarañados, Chusquea culeou

/ (right) Coihué de Magallanes, Nothofagus

betuloides.

Duck / ánade -

Helecho palmito grande (Blechnum magellanicum) - Canelo (Drymis winteri)

blossoms/ en flor.

The terrestrial fauna of mammals includes the guanaco

("the reindeer of the Ona indian"), one species of dog and two of

foxes, a hare of much appreciated skin (mistakenly called an otter, yet

piscivorous), numerous small rodents, hares, mice. Edentata and feline are

completely missed. In face of that poverty, many marine mammals exist: seals of

great variety, marine wolves and lions, dolphins, whales of many species, are

rife in channels and bays; several of them, already undergoing fatal

persecution.

Birds do well –

in enormous amounts. True clouds of cormorans, gulls, albatrosses, kind of

bustards or wading birds, goose, ducks, etc., thrive on the sea; other sorts of

birds prosper on land. Reptiles and amphibians are scarce. Yet there are

multitudes of fish of every sort in water salt and fresh. Insects, few (there

is an annoying tabano, and gnats too), but marine mollusks, crustaceans,

echinoderms, coelenterates – in fabulous masses.

Giant bladder kelp, Macrocystis

pyrifera

Fueguean flora

Vegetal life gravitates waterwards, too. The great

forests thrive at the foot of the ventisqueros,

on their humid effluvia; and at bottom of channels and bays the empire of the

seaweed spreads, on the greatest variableness seen in South America.

Branching of / Ramificaciones de Delesseria sanguinea

Near the coast the marine bottom resembles a garden,

brimful of "flowers" of every color down to where sunlight no longer

pierces anymore. Salt water being crystalline, the realm of seaweed blossoms with

magnificent pieces many meters in length: the giant bladder kelp Macrocystis pyrifera has individuals one

hundred meters long, that float in water forming small islands, perilous even

for large ships; other forms, colored from brown to yellow, violet, and reddish,

are "blossoming" Lessonia

[brown kelp, a Chromista], carmine, scarlet, or cherry-red Delesseria, laminariales, Ulva;

and still greater is the number of small seaweed down to microscopic

Chlorophyceae, and also Cyanophyceae [no longer counted as algae].

Chlamydomonas,

.01 mm wide / diez micras de ancho (left) - Sea lettuce, Ulva

lactuca; right photo, a detail.

An usual green alga, Chlamydomonas, produces the phenomenon of red snow, and another

combination the one of the green snow. More than 500 different species are

named and still many more remain unclassified.

Lessonia

Lessonia

On land, the forests of Nothofagus antarctica or Antarctic beech [leaves, blooms shown

below] impressed us. It is a tree with three varieties, one of perennial leaves,

others called there rivets (lenga)

and coihüe, forming forests that in

mountains grow up to heights of 300 and 400 meters, until dwarfed, dark-brown

forms, and lychen, continue them to greater heights, up to 1,500 meters, where

the winds' fury no longer lets any plant grow, neither low nor tall. The

forests reach an almost tropical density in the bays saturated of humidity and

defended from excessive cold.

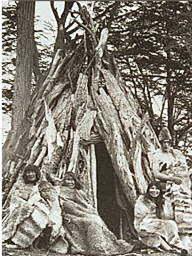

Onas hunting

in Tierra Del Fuego

Ona Indians

and their beech bark tee pee

.

Oliver

van Noort kills Yagans, kidnaps six; about January 1600 / Oliverio van Noort

mata yaganes, rapta cuatro muchachos y dos muchachas, hacia enero de 1600. Sus cartas

credenciales explicaban: “Nosotros, Mauricio, Príncipe de Orange, hemos

acondicionado estos Navíos que estamos enviando a las costas de Asia, África,

América y las Indias Orientales para negociar los tratados y comerciar con los

habitantes de estas regiones. Pero por cuanto hemos sido informados de que el

español y el portugués son hostiles a los asuntos de nuestras provincias, y que

están interfiriendo su navegación y comercio en estas aguas, contrariamente a

todos los derechos naturales de ciudades y naciones, nosotros damos órdenes

explicitas por la presente, para ir a esas islas, resistirse, hacer la guerra,

y golpear de cuantas formas sea posible contra el español dicho y portugués”.

“We, Maurice, Prince of Orange, have prepared these ships that We are sending

to the coasts of Asia, Africa, América, and the West Indies in order to

negotiate treaties and have commercial dealings with the inhabitants of those

regions. But as we have become noticed that the Spanish and the Portuguese are

hostile toward the affairs of our Provinces, and that they are interfering the

navigation and commerce in these seas, in a way contrary to all the natural

rights of cities and nations, We hereby put forward explicit orders to go to

those islands, resist, wage war, and strike in any and every way possible against

the said Spanish and Portuguese”. Newe

Welt und americanische Historien : inhaltende warhasstige und vollkommene

Beschreibungen über West Indianischen landschafften ... / durch Johann

Ludwig Gottfriedt. Franckfurt : Bendenen Meridianischen Erben, 1655. 661, [Abb. 3]

Aboard “Cap Polonio”

Before anything else we needed to fix the biological

suitcases: jars, bottles, tins, conservation liquids, phenol, nets, fishing gear,

shovels; the portable microscopic installation for the trip is indispensable.

And now, to the expedition. Good bye, Buenos Aires! Welcome Tierra del Fuego!

We left aboard the “Cap Polonio” (times changed), and arrived at Port Madryn.

We observed the loberías

(reproduction stations of marine wolves of one hair) in Port Pyramids and

fished in the gulf, gathering mollusks, crustaceans, isopodes, and in addition

an abundance of small pejerreyes, an

edible fish rife there. We arrived at Commodore Rivadavia; we visited fields of

petroliferous operation, although the xerophile flora of those barren lands,

and their marine fauna, interests us even more; the low tide affords us

echinoderms, marine starfish, variegated anemones, annelids, etc.

But it is necessary to exert yourself, climbing from

rock to rock: “with your face's sweat you'll earn your bread, the marine one as

well.”

We followed trip and entered the Strait of Magellan,

of low coasts, not much impressive; we arrived through narrow passages and known

sines to Punta Arenas, a considerable Chilean city, with a marine museum and

interesting collections of algae, that is the work of the Salesian priests. In

an excursion to the coast we collected the first units of blossoming seaweed,

that seemed to us otherworldly. We picked up everything that we was able to,

only to throw most the next day in exchange for better pieces.

HSDG „Cap Polonio“ auf

dem La Plata. Hintzer & Wulf, Hamburg 1.

In Port Harbeston we again visited the coast and forests.

We found a whale skeleton, eggs and nests of birds, enormous algae,

crustaceans, hydromeduses, colored polyps, briozoans of new species.

Hoste Island, seen by looking Southward from Tierra del Fuego Big Island

on the North

The trip follows the South now; we crossed the Hoste

island with its polyp-like peninsular forms, we cast anchor in the Orange bay;

the forests end by now, only some mosses and seaweed vegetate on the blackened

rocks swept by winds and waves. Next day we passed the centralmost point, the

terrible Cape of Hornos, with the sea calm and smooth like a mirror, and taking

now course toward the North, we crossed the island of the States with its

mountains horribly fractured, as well as the island of Año Nuevo; these are

regions inhabited by million birds, colonies of penguins and gulls, that in

mass cross the air, whereas in the ocean dolphins and whales travel in every

direction. Satisfied, we arrived at the Islas Malvinas: at home.

Dawn

/ Amanecer en el Estrecho de Magallanes.

Conclusion

But now the real work begins; we must select, review,

arrange the collections; classify with the microscope the species and

varieties, a chore not seldom unfeasible by lack of data.

We finish our excursion by insisting once more on the

urgent need, that the high authorities guard the integrity of the beauties and

natural products of the North as well of the South. By the same token we remark

that they must contribute more intensely so that the country's scholarly people

– and there are many – have the possibility of knowing those beauties and

natural products, and the Argentine youth of taking advantage of their lessons,

because only the acquaintance with the country and its vital forms awakes the

genuine love for it. Patriotism is to consist in deeds, not words. The most

efficient way to obtain this would be by organizing a national biological

institute, with a biological Museum and stations for practical work and

formation of collections, in the most important zones of the Argentinian North

and South. And the future biological station of Ushuaia will be among the

first. I look forward to a successor of Bernardo de Irigoyen, who may

inaugurate in Tierra del Fuego that scientific lighthouse.

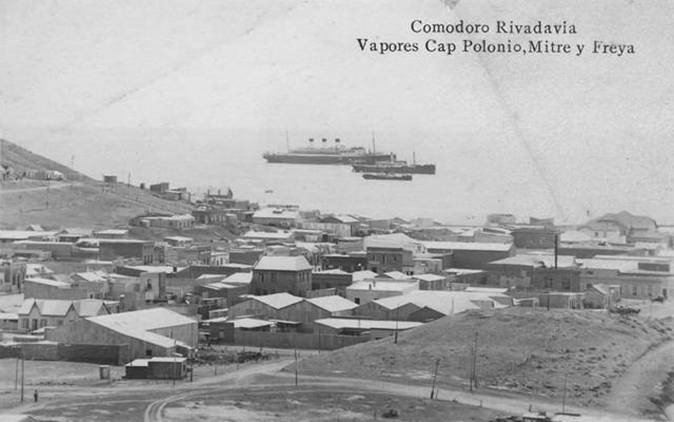

Comodoro Rivadavia.

Vapores Cap Polonio, Mitre y Freya. Foto Kohlmann. Artura.

Sunset,

Strait of Magellan / Atardecer en el Estrecho de Magallanes

Acknowledgements

The invaluable bibliographic help

received from Dr. Gabriel Tavridis of Stanford University, the Fundación Ramón Carrillo (Buenos Aires),

and Jakob's laboratory (Centro de

Investigaciones Neurobiológicas, Ministry of Health, Argentine Republic,

and Laboratorio de Investigaciones

Electroneurobiológicas, Buenos Aires City Govt.), is gratefully

acknowledged.

Bibliography

Chichilnisky,

S. (2005) Aventuras pampeanas en salud mental: historia de la psicología

clínica, psiquiatría y psicoanálisis en la Argentina. Parte primera: Viñetas. Electroneurobiología

13(2): 14-160.

Darwin, C. (1839) Journal of

Researches into the Natural History & Geology of the Countries Visited

during the Voyage of H.M.S. Beagle under the Command of Capt. Fitz Roy, R.N.

Henry Colburn, London.

Jakob, C. (1923) Elementos de

Neurobiología, volumen I: Parte Teórica. Biblioteca Humanidades, Facultad

de Humanidades y Ciencias de la Educación, Universidad Nacional, La Plata.

Jakob, C. (1926) Un viaje

biológico a Tierra del Fuego (Conferencia, Duodecima Sesión Ordinaria del 5 de

Septiembre). In: Ibarguren C., Padilla E.E., Ure E.J. (eds.) Anales del

Instituto Popular de Conferencias, Edición Oficial – Decimo Ciclo, Año 1924,

Tomo X. Administración Vaccaro, Buenos Aires, pp. 155-161.

Jakob, C. (1936a) Alrededor del

Tronador. Excursiones biogeográficas en la Suiza Argentina. Rev. Geogr.

Amer. 28: 1-21.

Jakob, C. (1936b) La Cordillera

Central Nevada (desde 6.000 metros de altura). Rev. Geogr. Amer. 38: 325-332.

Jakob, C. (1937a) Desde Bariloche

al Pacífico por el Vuriloche. El antiguo paso internacional del Vuriloche

reabierto. Rev. Geogr. Amer. 41: 75-90.

Jakob, C. (1937b) La fiscalización

de las reservas acuáticas andinas es una obligación nacional para la Argentina.

Rev. Geogr. Amer. 50: 313-326.

Jakob, C. (1937c) El Cordón de los

“Cuernos del Diablo” (Expediciones en zonas desconocidas del Nahuel Huapí). Rev.

Geogr. Amer. 46: 7-26.

Jakob, C. (1939) La floresta

andina de altura. Rev. Geogr. Amer. 67: 229-236.

Jakob, C. (1940) Hacia los

Ventisqueros Australes del Tupungato. Rev. Geogr. Amer. 79: 217-226.

Oddo, Vicente, and Szirko, Mariela (2006), El

Maestro dela medicina platense Christofredo Jakob, discípulo y amigo de Adolf

von Strümpell. Electroneurobiología

14 (1): 115-170.

Orlando, J. C. (1966) Christofredo

Jakob: Su Vida y Obra. Editorial Mundi, Buenos Aires, pp. 61-72.

Ross,

Peter (2007) The Construction of the

Public Health System in Argentina 1943-1955 - Construcción del Sistema de Salud

Pública en la Argentina, 1943-1955

(bilingual edition / edición bilingüe), Electroneurobiología 15

(5), accepted for publication.

_______

revista

Electroneurobiología

ISSN: 0328-0446