Gobierno de la ciudad de Buenos Aires

Hospital Neuropsiquiátrico

"Dr. José Tiburcio Borda"

Laboratorio de Investigaciones Electroneurobiológicas

y

Revista

Electroneurobiología

ISSN: ONLINE 1850-1826 - PRINT 0328-0446

The Biological Psychology of José Ingenieros,

some biographical points, and

Wilhelm Ostwalds (Nobel Prize Chemistry, 1909)

Introduction to the 1922 German edition

by

Lazaros C. Triarhou

Professor of Neuroscience and

Chairman of Educational Policy,

University of Macedonia,

Thessalónica 54006, Greece

Contacto / correspondence: triarhou[-at]uom.gr

and

Manuel del Cerro

Professor Emeritus of Neurobiology

& Anatomy and Ophthalmology,

University of Rochester,

Rochester, New York 14642, USA

Electroneurobiología 2006; 14 (3), pp. 115-195; URL

<http://electroneubio.secyt.gov.ar/index2.htm>

Copyright

© junio 2006 Electroneurobiología. Esta texto es un artículo de

acceso público; su copia exacta y redistribución por cualquier medio están

permitidas bajo la condición de conservar esta noticia y la referencia completa

a su publicación incluyendo la URL (ver arriba). / This is an Open Access

article: verbatim copying and redistribution of this article are permitted in

all media for any purpose, provided this notice is preserved along with the

article's full citation and URL (above).

Received: 31 May 2006

Accepted: 30 June 2006

Printing this file does not keep original formats and page

numbers. You can download a .PDF (recommended) or .DOC

file for reading or printing, either from here or / Puede obtener un archivo .PDF (recomendado) o .DOC

para leer o imprimir este artículo, desde aquí o de

<http://electroneubio.secyt.gov.ar/index2.html

SUMMARY: One of the earliest recorded works in Biological

Psychology was published in 1910 by Argentinian psychiatrist José Ingenieros (1877-1925),

Professor of Experimental Psychology at the Faculty of Philosophy and Letters

of the University of Buenos Aires. Ingenieros, a multifaceted personality and

prolific author and educator, has been considered a luminary for young

generations, ahead of his time, and was famous for his lapidary aphorisms.

Physician, philosopher and political activist, he was the first psychologist

who tried to establish a comprehensive psychological system in South America.

His long list of publications includes 484 articles and 47 books, which are

generally categorized in two periods: studies in mental pathology and

criminology (1897-1908) and studies in philosophy, psychology and sociology

(1908-1925). Some of his books continue to be published and to be best-sellers

in the Spanish-speaking world; however, his works were never particularly

available to English-speaking audiences. In the present study we present an

overview of Ingenieros life and work, and an account of his profoundly

interesting work Principios de Psicología Biologica, in which he

analyzes the development, evolution and social context of mental functions. It

is a hope, eighty years after his death, to bibliographically resurrect this

ardent champion of reason in the English biomedical and psychological

literature. We also provide the original German and an English translation of

the Introduction contributed by Nobel laureate Wilhelm Ostwald (1853-1932) to

the 1922 German edition of Ingenieros Biological Psychology, pertinent to the

energetic principles Ingenieros adopted and the study of Psychology as a

natural science.

![]()

1. Introduction

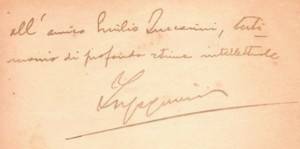

Fig. 1. José Ingenieros (1877-1925). Portrait from cover of

special issue of Nosotros (Editorial, 1925b). The signature in the lower

frame is from the dedication of doctoral thesis by Ingenieros to his friend

Emilio Zuccarini.

José Ingenieros (Fig. 1), one of

Argentinas estimable intellectuals, continues to be a highly read author in

Latin America to this day. Dubbed by del Forno (1950) luminary of a

generation (Fig. 2), Ingenieros has illuminated with his ideas the way to

generations of intellectuals, and continues doing so today. The scope of the

present study, a different version of which has already been published

(Triarhou and del Cerro, 2006) is two-fold. First, to introduce to the English

biomedical literature this champion of reason, at a time when the light of

reason appears pretty dim on much of a daemon-haunted world (Sagan, 1996);

second, to rediscover one of his earlier works, the Principles of Biological

Psychology (Principios de Psicología Biológica) (Ingenieros,

1913a), dating back to 1910 (Ingenieros, 1910b). That work went through six

editions in Spanish (Ingenieros, 1916a, 1919, 1937, 1946), and was also translated

in French (Ingenieros, 1914a) and German (Ingenieros, 1922a). Being the first

effort in South America to attempt to establish a comprehensive psychological

system, the work places special emphasis on the biological basis of mental

phenomena.

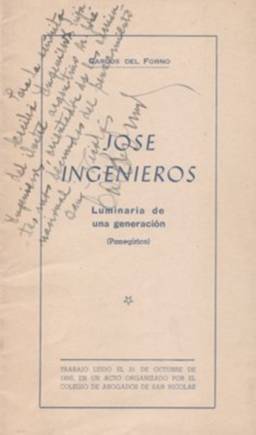

Fig. 2. Front page of lecture by del Forno (1950),

with handwritten dedication to Ingenieros daughter Cecilia.

Although it is not within the

scope of this article to provide a comprehensive review of the evolution of the

field of Biological Psychology as a discipline there are numerous books and

papers which do that (e.g. Reed, 1997; Rosenzweig et al., 1999; Birbaumer and Schmidt, 2003; Schandry, 2003) we

nonetheless note two landmark publications from two other pioneers in the brain

sciences. In a remarkable confluence, 1895 was an annus mirabilis for

coupling psychology with neurohistology, having seen the light of two independently

conceived works on neurobiological schemes of mental phenomena: Cajals

Conjectures on the anatomical mechanism of ideation, association and

attention (Ramón Cajal, 1895), and Freuds posthumously published theoretical

treatise Project for a Scientific Psychology (Freud, 1966).

In a striking convergence of

ideas, Freud, like Cajal, in the wake of certain theory of sleep being caused

by brain cells' amoeboidism, postulated that learning might produce prolonged

changes in the effectiveness of the connections between neurons and that such changes

could subserve a mechanism for memory. Updated, this view is still entertained

by neuroscientists as Eric Kandel (1981). Moreover, Freud (1966), in a manner

relevant to the scope of Ingenieros Psychology, wrote: The intention is to

furnish a psychology that shall be a natural science: that is, to represent

psychic processes as quantitatively determinate states of specifiable material

particles, thus making those processes perspicuous and free from

contradiction. According to Barondes (1993), Freud had in mind that the units

of such a natural science, the ‛specifiable material particles, would be

neurons, the cells of the nervous system, whose structure and organization he

had helped elucidate in his extensive neuroanatomical studies (Triarhou and del

Cerro, 1985; Shepherd and Erulkar, 1997; Guttman and Scholz-Strasser, 1998;

Pearce, 2003; Ochs, 2004).

In the aftermath of the fin du

siècle physicochemical and neurobiological repercussions on psychology,

books on Biological Psychology develop and expand ideas present in the

writings of

José Ingenieros. In the German literature there are the works of Lungwitz

(1925), Bleuler (1932) and Leonhard (1961), and the more modern accounts of

Birbaumer and Schmidt (1989), Köhler (2001), Gall et al. (2002), and Schandry (2003). In the French literature, one finds the works of Delmas-Marsalet (1961) and

Pellet (1999). Likewise, in the English literature, one encounters works by McDowall

(1941), Kimble (1973), Groves and Schlesinger (1979), Kalat

(1980), Hall (1983), Klein (1999), Rosenzweig et

al. (1999), Wickens (1999), Toates (2001),

Martin (2003), Pinel (2003), and Weiner et

al. (2003).

In Ingenieros Principios

we come upon the scheme of a synthetic system of psychology weaved from

positivist philosophy with a heavy emphasis on the science of experience

and the principles of physical chemistry, and inditing the phenomena of psychic

functioning at the ontogenetic, evolutionary and social levels, while leaving

some room for metaphysics. At a time when Psychology was still closely

associated with Philosophy, from which it had sprung or which, according to

another view, it had actually spawned (Reed, 1997) efforts to draw it towards

the principles of biological energetics and biological generative processes

should be welcomed with todays perspective.

It is refreshing, to say the

least, to find a clear proposition for psychology as a natural science,

presented almost a century ago by a highly learned and copious writer of opera

that span from politics to philosophy, through the way of neurology,

psychiatry, psychology, criminology, history, critical essay, morals and

sociology. In our opinion, Ingenieros deserves a place in the tradition of

physician-psychologists quod vide Ernst von Feuchtersleben, Wilhelm

Wundt, William James, Ivan Pavlov, Vladimir Bechterew, Sigmund Freud, Eugen

Bleuler, Alfred Adler, Carl Gustav Jung, Jean Piaget and the akin all the way

to Eric Kandel who have made valuable contributions to the emergence of

psychology as a biological science during its formative years in the 19th and

in the 20th centuries. We trust that the present report and its predecessor

(Triarhou and del Cerro, 2006) may signal the proper historical placement of Principios

among key historical works in Biological Psychology.

We provide the complete synthetic

conclusions of Ingenieros from the first Spanish edition (Ingenieros, 1913a)

and a translation of Ostwalds introductory commentary from the German edition

(Ingenieros, 1922a). We also provide some biographical data on Ingenieros and

Wilhelm Ostwald. Ostwald was the German chemist and philosopher, Nobel Prize

winner who contributed the Introduction to the German edition of Principios, and whose physical theories

Ingenieros refers to in five of the ten chapters of his book.

2. Life and work of José Ingenieros

(1877-1925)

2.1. Biographical note

Numerous biographies of José

Ingenieros have been published (Barreda, 1925; Colmo, 1925; de la Mendoza, 1925;

Fernández, 1925; Bermann, 1925; 1926; 1929; 1933; Mouchet, 1925; Mouchet and Palcos, 1925; Ramos, 1925; Schiaffino,

1925; Zavalla, 1925; Riaño Jauma, 1933; del Forno, 1950; Bagu, 1953; 1963; Ponce, 1957;

Torchia-Estrada, 1967; Gottheld, 1969a; 1969b; Laplaza, 1977; Ardila 1989;

Rodriguez Kauth, 1996; Díaz Araujo, 1998; Murillo-Ramos, 2001). Furthermore, Ingenieros daughter, writer Delia

Ingenieros de Rothschild (pseudonym Delia Kamia), produced an Anthology

(Kamia, 1961), which also contains a biographical note. A synoptic timeline of

Ingenieros life and corresponding world events is given in Table 1.

José Ingenieros was one of two

sons Pablo was the other of Salvador (don Salvatore) Ingegnieros

(1848-1922) and Mariana (doña Ana) Tagliavía, a family including Tagliavías

father José of revolutionary tradition and friends of Mazzini, Garibaldi, and

Malatesta. Although there is not a perfect agreement in the available records

(reviewed in detail by Díaz Araujo, 1998), the most likely scenario is that

Giuseppe Ingegnieros was born on 24 April 1877 at Vía Candelaí № 45,

Palermo, Sicily (Fig. 3). The original last name of the family, Ingenieros, was

Spanish in origin, and had been semi-italianized to Ingegnieros at the time

of emigration to Sicily prior to Salvadors birth there; it was

re-castillianized by José Ingenieros after 1912 for his European

publications.

|

|

Ingenieros

life and work

|

Events in science and

the world scene

|

|

1900 |

Graduates from Medical School; H.G.

Piñero establishes Psychological Laboratory at University of Buenos Aires |

Freud publishes Die Traumdeutung; Max Planck develops quantum

theory; Lewandowsky coins term blood-brain barrier |

|

1902 |

Founds Archivos de

Criminología, Medicina Legal y Psiquiatría |

Kennelly and Heaviside discover ionosphere; Cuba becomes independent

from Spain |

|

1903 |

Publishes Simulación de

la Locura and La Simulación en la Lucha por la Vida |

De Vries discovers mutations in plants;Wright brothers make first successful flight; Panama gains independence |

|

1904 |

Appointed Professor of Psychology; awarded

National Academy of Medicine Gold Medal |

Pavlov awarded Nobel Prize in Medicine; Russo-Japanese War (1904-1905) |

|

1905 |

Travels to Europe (1905-1906). Entertains

racist views about the poor, the Black, etc., later rejected. |

Einstein publishes Special theory of

relativity; Norway peacefully gains independence from

Sweden |

|

1906 |

Returns

to Buenos Aires |

Cajal and Golgi awarded Nobel Prize in

Medicine; Jakob

starts modelling brain higher functions on the interference of stationary

waves; Sherrington publishes Integrative action

of the nervous system |

|

1907 |

Founds

Instituto de Criminología de la Penitenciaría Nacional |

Mauritania makes maiden voyage from Liverpool to New York; Russian Alexander Scriabin composes Le Poème

de lExtase |

|

1908 |

Professor

or Experimental Psychology; forms Sociedad de Psicología; publishes Sociología

Argentina |

Austrian Gustav Mahler composes ninth

symphony; Salvador Allende born in Valparaiso |

|

1909 |

Elected President of Argentina Medical

Association |

Ostwald awarded Nobel Prize in Chemistry; Brodmann publishes Vergleichende

Lokalisationslehre der Großhirnrinde; Freud visits Clark University |

|

1910 |

Separate

chapters of Psicología Genética appear in Argentina Médica;

article Psicología Biologica appears in Archivos |

William James dies in Chocorua, N.H.; Titchener publishes A text-Book of

Psychology; Mexican Revolution (1910-1917); Portugal proclaimed a Republic; Tolstoy dies near Caucasus |

|

1911 |

Publishes

Psicología Genética; self-exile to Europe (1911-1914) |

Cajals Histologie du système nerveux published

in Paris; Jakob publishes a brain circuit better known

on Papez' 1937 description; Bleuler

coins term schizophrenia |

|

1912 |

Visits

European Universities |

Balkan

Wars (1912-1913); Titanic sinks |

|

1913 |

Principios

de Psicología Biológica and El Hombre Mediocre published in Madrid |

Watson

publishes article in Psychological Review; Albert Schweitzer builds Lambaréné Hospital in

Gabon |

|

1914 |

Marries Eva Rutenberg; Principes de

Psychologie Biologique published in Paris |

Cajal

completes publication of Degeneration

and regeneration in

Madrid with support from Spanish physicians of Argentina; outbreak

of WW I |

|

1915 |

Founds

Revista de Filosofía |

Romain Rolland awarded Nobel Prize in

Literature; Lusitania torpetoed by German U-boat off coast of Ireland |

|

1916 |

Attends

Washington, D.C. conference; publishes Criminología; fifth edition of Principios

de Psicología in Buenos Aires |

Einstein publishes General theory of

relativity; Argentinian composer Alberto Ginastera born; Britannic

sunk after striking mine in Aegean Sea |

|

1917 |

Professor

of Ethics; publishes Hacia una Moral sin Dogmas |

DArcy Thompson publishes Growth and form;

Russian Bolshevik Revolution |

|

1918 |

Publishes

Proposiciones Relativas al Porvenir de la Filosofía |

Max Planck awarded Nobel Prize in Physics;

end of WW I |

|

1919 |

Meets

President Hipólito Yrigoyen; sixth (final) edition of Principios de

Psicología published in Buenos Aires |

Watson publishes Psychology from the

standpoint of a behaviorist; Treaty of Versailles signed |

|

1921 |

Publishes

Los Tiempos Nuevos |

Einstein awarded Nobel Prize in Physics;

Argentinian composer Ariel Ramírez born |

|

1922 |

Father

dies. Writes Las Fuerzas Morales. Prinzipien der Biologischen

Psychologie published in Leipzig |

Neurobiologist Fridtjof Nansen awarded Nobel

Peace Prize; Jacinto Benavente awarded Nobel Prize in Literature; U.S.S.R.

established |

|

1925 |

Travels to México and France; dies in the

morning of 31 October from complications of meningitis |

von Economo and Koskinas publish Die

Cytoarchitektonik der Hirnrinde des erwachsenen Menschen, paying homage

to Cajal, Kaes, and Christfried Jakob |

Table 1. Timeline

of events in José Ingenieros life, and parallel events of relative interest in

neurobiology, science and the international scene during the first quarter of

the 20th century.

Fig.

3. Ingenieros as a child at ages 3, 4, 7 and 11,

photographed, respectively, in years 1880 (photography by Giannone, Palermo),

1881, 1884 (photography by J. Vigouroux, Montevideo) and 1888. (Sources: first

and third photographs, Fernández, 1925; second and fourth photographs, P.

Ingegnieros, 1927).

The family moved from Italy to

South America soon after Buenos Aires had

become the Federal Capital in 1880.

According to brother Pablo, José received his first instruction in Montevideo,

Uruguay in 1881 at the age of four years (Fig. 3), under the direction of the

notable educationist Aurelia Viera (P. Ingegnieros, 1927). In 1885 he was

enrolled in the Instituto Nacional, directed by educationist Pedro Ricaldoni.

The family settled in Buenos Aires in September 1885. Already a child prodigy

at age seven (Fig. 3), Ingenieros completed his primary education at the

Catedral al Norte (not yet an elegant quarter) and in 1888 was enrolled in

the Colegio Nacional Central de Buenos Aires, obtaining the baccalaureate in

1892. His father, a journalist, had a book shop, and urged his son José to

read, write, correct proofs and translate into English, Italian and French from

early on; he was already translating Petrarca at eight.

Fig.

4. (Upper) Ingenieros giving a neurology lecture in

San Roque Hospital, today Ramos-Mejía, in 1903 (from P. Ingegnieros, 1927). (Lower)

A 1910 photo with colleagues José María Ramos-Mejía, Francisco de Veyga and

Lucio V. López (from Fernández, 1925).

In 1893 Ingenieros entered the

University of Buenos Aires. In 1897 he obtained a degree in Pharmacy, and in

1900 he graduated from the Medical School. As a medical student, he

collaborated with the review Atlántida. In 1898, he had the opportunity

of meeting José María Ramos-Mejía, who started as being his professor and with

whom he ended up maintaining a close friendship (Fig. 4).

Ingenieros married Eva Rutenberg

in 1914 (Fig. 5); they had four children, Delia, Amalia, Julio and Cecilia.

Nevertheless, he did not resign thereby all of his habits as a bachelor. Poet

Eduardo Moreno (1906-1997) recalled, «A review of my teen years: listen, I

already frequented the dancehalls around Plaza Italia and one night I saw José

Ingenieros and also a man of letters, Alberto Ghiraldo, entering a local called

"Palermo" located one block from Santa Fe Avenue. They were going to

that venue to dance tango. They, as well as many others at that time, had a

passion for tango. Tango was not plebeian, it did not belong only to the

neighborhood or the tenement houses. That is something to highlight.»

Fig. 5. (Upper) Ingenieros in 1913 in

Switzerland during his engagement to Eva Rutenberg (from Barreda, 1925). (Lower)

With wife Eva and four children in April 1925, before his trip to Europe and

México (unpublished photograph provided by Caras y Caretas magazine to

Barreda, 1925).

José Ingenieros died at 7:00 in

the morning of 31 October 1925 at Calle Cangallo

1544, Buenos Aires, at the age of

48 years (Fig. 6). Based on the observed symptoms, which had been related by

Ingenieros himself, medical colleagues of the time suspected a severe

meningitis that resisted treatment with an eventual loss of consciousness,

result of an earlier sinusitis, frontal neuritis and nasal abscess. With his

last act culminated Ingenieros anticipated desire in Las fuerzas morales

(published posthumously), to have the happiness of dying before aging. His

wife Eva survived him by 30 years; their young daughter passed away in 1995 and

the eldest in 1996.

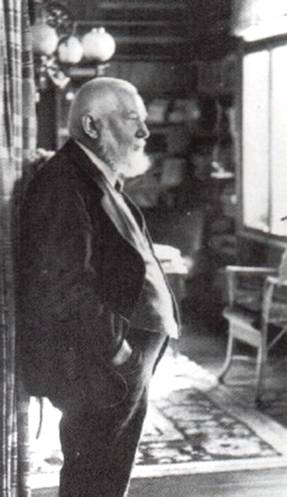

Fig. 6. Last portrait of José Ingenieros (left),

a few days before his death in October 1925 at the age of 48 years (from P.

Ingegnieros, 1927); the last manuscript of Ingenieros

(right), the prologue written in 1925 for Las fuerzas morales (from

Editorial, 1925b).

Among the many commemorations for Ingenieros,

at least three journals dedicated special issues posthumously (Editorial, 1925a; Editorial, 1925b; Editorial, 1933). To honor the name of José Ingenieros, the Cultural

Center of the Faculty of Medicine of the

University of Buenos Aires was named after him (Centro Cultural José Ingenieros, Facultad de Medicina, Universidad de Buenos Aires,

Paraguay 2155, Buenos Aires, Argentina, www.fmed.uba.ar/cultura), as well as a popular sector

of the Buenos Aires conurbation, many streets, and cultural associations across

the country.

2.2. Academic

posts

Ingenieros dedicated his first

professional efforts to nervous and mental pathology. He was named Head of the

Clinic of Nervous Diseases (Clínica de Enfermedades Nerviosas) of the Faculty

of Medicine of the University of Buenos Aires. The Laboratory for the Clinic

was located in the insanes' asylum and it was directed by German-born

neuropathologist and neurobiologist Christfried Jakob (who took on Argentinian

citizenship as Christofredo Jakob, 1866-1956). Jakob taught Ingenieros

neurohistological techniques. Ingenieros often attended Jakob's lectures,

worked in the Laboratory, and was also present at the Service of Observation of

the Mentally Ill of Argentinas Federal Police (Servicio de Observación de

Alienados de la Policía Federal Argentina), which he

would head as Director two years later. Ingenieros proposed for the first time to open

outpatient units in public institutions for the treatment of neurasthenia,

hysteria and other diseases that did not require hospitalization, and he held

the view that public hospitals should serve for education and practice. Between 1902 and 1903 he offered courses in Neuropathology and

Clinical Semiology at the Faculty of Medicine (Fig. 4).

In 1904 Ingenieros substituted as

Professor of Psychology at the Faculty of Philosophy and Letters of the

University of Buenos Aires. In 1908 he obtained the Chair of Experimental

Psychology in the Faculty of Philosophy and Letters.

On 30 May 1911 the Governing

Council of the Faculty of Medicine nominated him unanimously from the list of

candidates for the Chair of Legal Medicine. In making the final decision, the

President of Argentina (at the time Roque Sáenz-Peña) vetoed the nomination and

instead appointed the second runner-up. The episode caused Ingenieros to openly

express his anger against the President in a public letter. Ingenieros

considered such an act of interference as government immorality, and treated

Sáenz-Peña as the implied mediocre man in his book El hombre mediocre

(Ingenieros, 1913b; 2001). He distributed his books among friends and

institutions, and moved to Europe in a self-imposed exile between 1911-1914, to

return to Argentina three years later, after Sáenz-Peñas death.

In 1917, due to a temporary

absence of Dr. Rodolfo Rivarola, he occupied the Chair of Ethics, and worked on

developing the definitive form of his book Hacia una moral sin dogmas

(Towards an ethic without dogma) (Ingenieros, 1917). In 1918 he was named

Academician of the Faculty of Philosophy of the University of Buenos Aires. For

this opportunity he prepared as a discourse his Proposiciones relativas al

porvenir de la filosofía (Ingenieros, 1918), a text directed at

transforming philosophical studies. Yet

the meeting was adjourned due to

the University Reform's turmoil, the new academician being received without

reading it. Although Ingenieros did not directly participate in the Reform

Movement, he did give his support to the students, and later, reformist leaders

underscored his intellectual influence in their generation. After World War I

he became Vice Dean of the Faculty of Philosophy and Letters. Ingenieros

resigned all teaching and administrative posts at the University of Buenos

Aires in 1919.

2.3. Travels in the Americas

In 1901 Ingenieros travelled to

Uruguay to participate in the Second Latin American Scientific Congress held at

Montevideo. In 1916 he attended the Second Panamerican Scientific Congress in

Washington, D.C., by special invitation from the Carnegie Endowment for

International Peace. There he presented a paper entitled La Universidad del

porvenir (The University of the future) (Ingenieros, 1916b), which in the

meantime had also been published in Spain by Vértice Editorial, Barcelona. In

1925, in a special invitation from the Mexican government, he visited México

and was named distinguished guest.

Fig. 7. Ingenieros at Rome, walking through the

Campidoglio's doorway to participate in the 1905 Psychological Congress (upper),

and with novelist Manuel Gálvez (middle) (from P. Ingegnieros, 1927 and

Schiaffino, 1925, respectively). Walking in Paris during the same year (lower)

in the company of cartoonist-caricaturist Pedro Zavalla, known as Pelele (from

Zavalla, 1925).

2.4. Travels to Europe

Ingenieros made three trips to

Europe, when he was 28, 34 and 48 years old. The first trip, between 1905-1906,

was to attend the Fifth World Congress of Psychology in Rome (Fig. 7), where he

chaired the Session on Pathological Psychology. Taking advantage of being in

Europe, he spent time in Spain as well. He visited European Universities,

lecturing on topics in his specialty, and contributed articles to professional

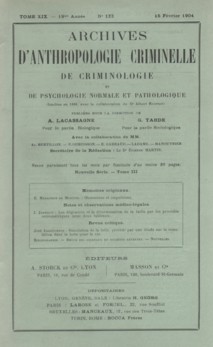

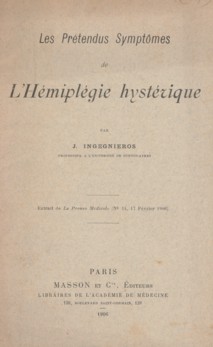

journals (Figs. 8, 9), such as Archives dAnthropologie Criminelle (Ingenieros,

1904a), Revue Neurologique (Ingenieros, 1905a), La Presse Médicale (Ingenieros,

1906a), as well as Nouvelle Iconographie de la Salpêtrière, Revue de

Psychologie, Rivista di Sociologia, Neurological Journal and Prese

Medicala Romana, before returning to Buenos Aires in 1906 (P. Ingegnieros,

1927; Ponce, 1957; Van Der Karr and Basile, 1977).

He compiled the impressions from

his two years in Europe in a series of non-scientific articles in two versions

entitled At the margin of science, which was published in Valencia

(Ingenieros, 1906b), and Crónicas de

viaje (Ingenieros, 1908). The latter work has been criticized by some

undeniable racist portrayals of the poor, the native and negros encountered in the travel's scale ports, which portrayals

Ingenieros later rejected and criticized himself. Rodríguez Kauth (1996) calls

this travel's period a "stage of cognitive dissonance". The first

version includes brief essays, commentaries and discourses, many of which had

appeared in Buenos Aires in the newspaper La Nación, and were

complementing the series of articles also published in Valencia in the book Italy

in science, life and art (Ingenieros, 1905b).

Upon his return to Argentina, he

tried to tie to the high society of Buenos Aires and to join the Jockey Club.

He was not accepted. Some say that a socialist and (outspokenly) atheist was

not what the Jockey Club, the ultimate inner circle of the rich and powerful,

wanted as a fellow member; others, that Ingenieros

had indiscreetly revealed that a relative of a Commission's member had been his

patient.

When the Chair in Legal Medicine

was not granted to him, he went on his second European trip, between 1911-1914:

his self-imposed exile. In the course of that period, he expanded his

scientific studies at the Universities of Paris, Geneva, Lausanne and

Heidelberg, and systematically began to give room to his philosophical

inquietudes. He again spent time in Spain, editing and publishing, among other

works, the 1913 Madrid editions of El hombre mediocre (Ingenieros,

1913c) and Principios de Psicología Biológica (Ingenieros, 1913a).

His third and last European trip

took place in 1925 as a guest of the French Government in order to attend the

festivities marking the centennial of Charcots birth. He returned to Buenos Aires in

September 1925, the month before his demise.

Fig. 8. Ingenieros

in 1905 in Paris with Payo Roqué (left) and in casual conversation with

General Julio A. Roca (right). Pictures tell much more about the man

than any text. For a 28-year old Argentinian to be in Paris, it was an

unequivocal demonstration of personal success. Further, the intellectual,

ultraliberal professor, is chatting with the General former president Roca,

embodiment of the most rancid Argentinian oligarquía (from Colmo, 1925).

Fig. 9. Frontispiece of French journals where articles

appeared in 1904 and 1906 (Ingenieros, 1904a; Ingenieros, 1906a).

3. Publications

and other intellectual activities

3.1. Scientific journals and

literary works

In 1899 Ingenieros joined the Revista de Criminología Moderna. That same year he was discovered by a would-be

friend, professor and mentor, Dr. Francisco de Veyga (Fig. 4), who designated

him secretary of redaction of La Semana Médica (Medical Weekly), which

would see him as one of its regular collaborators.

In 1900 he reported his work in

Psychopathology and Criminology in a small pamphlet under the title Dos

páginas de Psiquiatría Criminal (Ingenieros, 1900). Another one of his

first publications, shortly after graduating from Medical School, was a famous

critical essay about the book La Ciudad Indiana (The Indian City) by

Juan Agustín García; the essay appeared in Revista de Derecho, Historia y

Letras (Review of Law, History and Letters).

In January 1902, at the suggestion

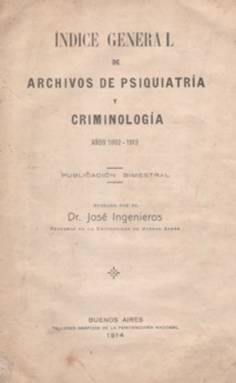

of de Veyga, Ingenieros co-founded with Ramos-Mejía the journal Archivos de

Criminología, Medicina Legal y Psiquiatría. A bimonthly publication, it was

the official journal of Sociedad de Criminología (Society of Criminology). In 1903 the

title of the journal was changed to Archivos de Psiquiatría y Criminología

Aplicadas a las Ciencias Afines and continued to be published regularly

under the editorship of Ingenieros until December 1913 (Fig. 10). During the

years of his editorship, Ingenieros himself contributed to the journal 90

articles (Ingenieros, 1914b); the topics he covered were diverse, ranging from

the physiology of the cerebellum (Ingenieros, 1905c) to the pathology of

psychosexual functions (Ingenieros, 1910a) and the psychology of genius

(Ingenieros, 1911c). His very first article on Biological Psychology appeared

in 1910 (Ingenieros, 1910b), and all the remaining chapters of the book under

the title Genetic Psychology appeared the following year (Ingenieros, 1911a).

In 1911, Ingenieros also published in the Archivos the first version of

six of the eight chapters of El hombre mediocre (Ingenieros, 1911b).

Fig. 10. General index of Archivos de Psiquiatría y

Criminología for 1902-1913, the years that Ingenieros edited the journal.

Articles in the Archivos of

especial interest, by other authors, include those of Argentinian philosopher

and writer Macedonio Fernández (1874-1952) on the problem of genius (Fernández,

1902) and by Christofredo Jakob on the relationship of psychology to cerebral

histology and cortical biology (Jakob, 1911; 1913). Ingenieros also solicited

or reproduced articles by European authors, including one of Cajals classical

essays on the neuron doctrine (Ramón y Cajal, 1907).

In 1913, while in Europe,

Ingenieros announced to Helvio Fernández that he was suspending the publication

of Archivos. Fernández continued the journal as the Revista de

Criminología, Psiquiatría y Medicina Legal, a title maintained from 1916 to

1935, a period in which Jakob published his neurobiological synthesis on the

issue of memory; from 1936 to 1950, the journal became Revista de

Psiquiatría y Criminología (information based on the Catalogues of

Periodical Publications of the National Academy of Medicine of Buenos Aires and

the Library of the School of Medicine of the University of Zaragoza).

Fig. 11. (Left) Ingenieros in 1904, the year

following publication of La Simulación de la locura (from Colmo, 1925).

(Right) Frontispiece of book resulting from his doctoral thesis

(Ingenieros, 1903). (Next page) 1923

Greek translation by Dr. A. G. Dalezios, Georg I. Vasileiou Publishing House

(Philosophical and Social Library, no. 15), Athens.

In 1904 the National Academy of Medicine

of Buenos Aires awarded Ingenieros the gold medal (Premio de la Academia de

Medicina) for best medical work published nationwide, for his book La

simulación en la lucha por la vida, which had formed his doctoral thesis

where he affirmed that the struggle of

the classes is one of the manifestations of the struggle for life and Simulación de la locura. Those two works,

included in a single 500-page long book (Fig. 11), probably the first South

American book on feigned insanity, were published by La Semana Médica

(Ingenieros, 1903). An Italian translation of the work was published a year

later in Torino (G. Ingegnieros, 1904). A

critical review of the work consisting of the synthetic conclusions of the

two studies appeared in French (Ingenieros, 1904a) that same year (Fig. 9). A

Greek translation of the book was published in Athens two decades later

(Ingenieros, 1923).

From 1904 on Ingenieros published

studies dealing with hysterical phenomena (Ingenieros, 1904b, 1906a) and their

relation to art as well, particularly music (Ingenieros, 1907). The work was

honored by the Medical Académie de

Paris. In this framework, he contended that "the auditive, visual,

phonative, and graphic images special of the music language are localized in

anatomical sub-centers included, respectively, within the centers of Wernicke,

Kussmaul, Broca and Exner, accounting for the localizations for every kind of

performance, such as violin and piano." This sharply factual presentation

was contested by a disciple of Jakob, José Tiburcio Borda (18691936), as being

rather a theoretical supposition, not yet enough grounded on empirical results.

(The divergence created some mutual reserve, which did not prevent to

collaborate again after the 1910 American Scientific International Congress.

Following the Congress Jakob himself was invited to contribute to the Archives). Ingenieros based his

criticized studies on the work of Charcot and Janet, and also made references

to the work of Breuer and Freud. Francophile Ingenieros initially received

Freud through French authors, specially the well-known critique that Pierre

Janet dedicated to Freud in 1913. His 1919 book Histeria y sugestion

sold repeatedly in several editions, at a time when many Argentinian

intellectuals were going back and forth to Europe, especially Paris, and

growing an increasing interest in unconscious and dream phenomena (Vezzetti,

1996; Puig 2004). Later on Ingenieros abandoned psychotherapy and wrote La

locura en la Argentina (Madness in Argentina), centering his interest on

dementias as a social phenomenon.

In 1908 Ingenieros founded the Sociedad

de Psicología (Society of Psychology); its first President was the eminent

researcher Horacio G. Piñero, who in 1900 had established the first

Psychological Laboratory in the University of Buenos Aires. Ingenieros was

elected President of the Argentina Medical Association in 1909 and President of

the Society of Psychology in 1910.

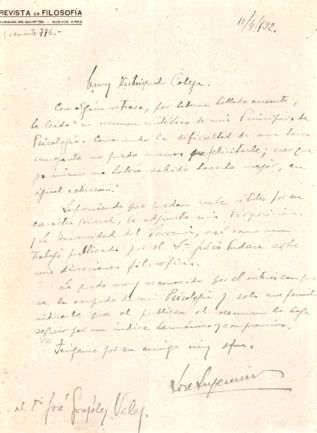

In 1915 Ingenieros founded the

journal Revista de Filosofía, which continued publication until 1929

(Ingenieros and Ponce, 2000). In 1915, Ingenieros also produced, in association

with Severo Vaccaro, a popular rather than academic collection, entitled La

cultura argentina. Between May and June 1916 he published the complete text

of La cultura filosófica en España (Philosophical Culture in Spain) in Revista

de Filosofía (Ingenieros, 1916d).

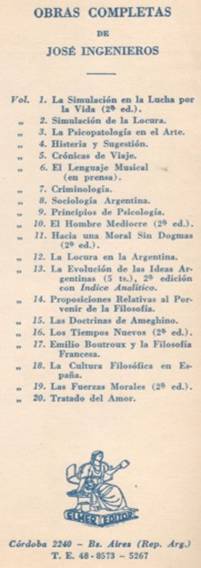

The Complete Works (Obras

Completas) of José Ingenieros were published in 20 volumes by Elmer Editor

in Buenos Aires in 1957 (Ingenieros, 1957a); the list of titles is reproduced

in Fig. 12. Another edition, in 8 volumes, gathered on the basis of the

compilation of Ingenieros, and of Aníbal

Ponce after Ingenieros death, was

published by Mar Océano in 1962, with

prefaces and the collaboration of Julio L. Peluffo, Héctor P. Agosti and

Gregorio Weinberg (Ingenieros, 1962).

Fig.

12. Titles of books contained in the 20-volume 1957

edition of Obras Completas by Elmer Editor.

3.2. Political activity

As a medical student, on 7 December 1894 Ingenieros was

appointed secretary of the University

Socialist Center. It had been formed by renowned socialist Juan B. Justo (1865-1928), who later married another physician,

Ingenieros' friend and Jakob's student, socialist activist Alicia Moreau.

Ingenieros published the first piece of his noteworthy work ¿Que es el

Socialismo? (What is Socialism?) on 1 May 1895 in the periodical La

Vanguardia. He also directed the left weekly magazine La Montaña and by then wrote that money was dirty

and infectious. Nonetheless, in 1902 he was invited to resign affiliation

with the Socialist Party, after attending one of their gatherings in black tie

outfit. As Ángel Rodríguez Kauth is probably right in calling

this vital stage one of cognitive dissonance, one may be sure that such

outfit was not intended to upset his comrades. By then and until around 1910

Ingenieros distinguished himself by his refined attire, as shown in the winter

photographs: immense frock-coat, stovepipe hat, giant white collar, red

waistcoat, and sometimes a gold breastpin with the sportful legend, "Arbiter Elegantiarum".

In

1903 Ingenieros was designated, by the Municipality of the City of Buenos

Aires, as a Commissioner with the aim of studying the hygienic and social conditions

of the working and marginalized sectors. His diagnostic proposal was considered

a monument of socialist thought on the topic.

In 1919 Ingenieros accepted an

interview with President Hipólito Yrigoyen who was beginning a 14-year period in government, having won elections with his Radical Party, after a

Roque Sáenz Peña's initiative introduced

the secret ballot in 1916 in order to exchange opinions with him on the social

and political crisis that the country was experiencing. A written account of

the encounter has been given by Ingenieros daughter Delia (Kamia, 1957).

In 1920 Ingenieros adhered to the

progressive group Claridad (=Glasnost!) that Anatole France and other

intellectuals had founded in France. In his 1921 work Los Tiempos Nuevos

he defended the Bolshevik Revolution and was critical of the intervention

policy of the United States in Latin America. In 1922 he proposed the

foundation of Unión Latinoamericana (Latin American Union). In 1923 he

founded a monthly, Renovación, an anti-imperialist combative organ. He

used to sign under pseudonym Julio

Barreda Lynch (not to be confused with his young friend Ernesto Mario

Barreda, 1899-1958) or Raúl H. Cisneros.

In 1925 he co-authored, with socialist leader Alfredo L. Palacios, the founding

act of Unión Latinoamericana, and forswore his crude racist declarations of

yore, some affirming that Blacks seemed "closer to apes than to civilized

men, ... All that is done in favor of the inferior races is anti-scientific. At

most, one might protect them so that they die out agreeably." Unforeseen

death prevented him to accordingly revise his old stick-in-the-mud lines.

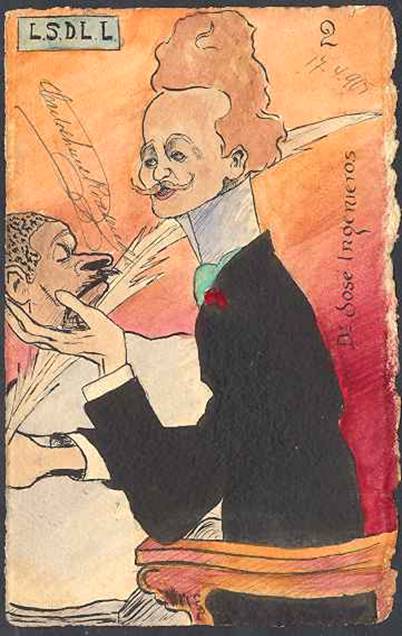

Fig. 13. Social critique: an Argentinian postcard

dated 1905 (previous page) satirizes the fact that by the time José Ingenieros,

a well-known public figure, had been unable to relinquish descriptive distance

when dealing with certain human groups. This "lack-of-empathy"

critique of late grew into insisting that he thereby helped to make persuasive the consensus about existing social exclusions. Such demeanor, at times, is contrasted with the acts of

another neurobiologist in the same Argentine tradition, Ramón Carrillo

(1906-1956), who as the comparison has it as a Minister of Health did not

reinforce a sector's polítical

hegemony by stigmatizing the disqualified social sectors

("medicalization"), portraying them in exclusion-legitimating

biological scenarios. In order to include and protect the whole population

Ramon Carrillo built some 400 hospitals or sanitary public institutions not

precisely contributing to the survival of the fittest and decentralized their

operation. Yet not always is stressed

that Ingenieros did not enjoy any similar power, and that he retracted his

former views on the mentioned human groups.

3.3. Studies in

Criminology

In 1896 Ingenieros wrote some

essays on Sociology and Cultural Anthropology. He had already begun to show

signs of his later professional and intellectual curiosities. The writings

unfolding in Criminología were united for the first time under Dos

páginas de Psiquiatría Criminal (Ingenieros, 1900). He inaugurated Archivos

de Criminología, Medicina Legal y Psiquiatría with his article Valor de la

psicopatología en la antropología criminal (Ingenieros, 1902), which was to

form the basis for developing his later and quite famous text Criminología

(1916c) that would be published in seven editions by 1919 (Ingenieros, 1957b;

1962).

Essays, written between 1899 and

1901, had by 1905 been reorganized and translated into English, French,

Portuguese and Italian, and published in various reviews. Most of these

appeared in Italian in a volume entitled Nuova classificazione

psicopatologica dei delinquenti (G. Ingegnieros, 1907); a Spanish

translation not mentioning a translators name appeared in Peru without

knowledge of the author (Ingenieros, 1908). After corrections and additions,

the work was re-edited for the Institute of Criminology of Buenos Aires and

published in 1910 by the Imprenta de la Penitenciaría Nacional (Press of the

National Penitentiary Institute), in which inmates were working as a part of

their rehabilitatory training. Including the part on Criminal Psychiatry, it

was reprinted two years later in Madrid under the title Criminología (Ingenieros,

1912). A sixth edition appeared in 1916 in Buenos Aires (Ingenieros, 1916c);

that text forms Volume 7 of the 1957 edition of Obras Completas (Ingenieros,

1957b) and was used for a Portuguese translation by Brazilian Professor Haeckel

de Lemos as well.

On 6 June 1907 Ingenieros founded

the Institute of Criminology of the National Penitentiary of Buenos Aires

(Instituto de Criminología de la Penitenciaría Nacional de Buenos Aires), a

clinic for the study of criminals and mental patients, of which he became first

director, an office he held until 1914

(del Olmo, 1999; Sánchez Sosa and Valderrama-Iturbe, 2001). As director

of the Servicio de Observación de Alienados at first, and heading the Instituto

de Criminología subsequently, he kept collecting and revising his material

over ten years, also taking into account contemporary European criminological

doctrines. In the spirit of the Positive School he pointed to the influences

of the modern philosophy of law, taking into account the biological and

sociological bases that form the foundations of Criminal Jurisprudence, and

transforming Criminal Anthropology into a Criminal Psychopathology by defining

the social value of criminal behavior and by providing a new classification of

criminals based on clinical observations.

Criminology covers topics such as the new philosophy of law and

criminal law, the crisis of contemporary penal legislation, postulates and

program of criminology, causes of criminality, the value of psychopathology in

criminal anthropology, the psychopathology and social unadjustment of

criminals, clinical and psychological fundamentals and psychopathological

classification of criminals, the theoretical postulates of juridical

positivism, the new bases of social defense, criminal psychiatry and the

dangers of defective penal legislation. Of special interest is the proposition

that ethical norms are constituted as a result of social experience

In

higher animal species, the fact manifests in a hundred ways that can be read in

the treatises of anecdotal Zoology or a Zoological Psychology. In humans

we observe it in every instance (Ingenieros, 1957b; Díaz Araujo, 1998).

To understand Ingenieros position

and impact, one has to consider the sociopolitical situation in Argentina at

the time of his most prolific criminological activity. One of his main concerns

was immigrants (Peset, 1983); moreover, his theoretical conclusions were drawn

from the study of prisoners, most of whom were immigrants, in this case white

anarchists. As mentioned, like other members of the Enlightened Minorities of

the 1880s generation, also Ingenieros expressed certain prejudices in some of

his works. Yet he attempted to explain criminality in psychopathological terms.

Such a

wave of massive migration was taking place in Argentina that, by 1890, the

country was receiving more

foreigners than any other Latin American nation. It is estimated (Rock, 1977)

that between 1857-1916, over 4,750,000 immigrants entered a country that would

in the years to come be marked by an unstable society, oligarchy, conflicting

relations between ruling class and immigrants, the resonance from the world

financial crisis of 1890, workers overexploitation, abominable urban living

conditions and increased crime among the immigrants' concentration around the

port of Buenos Aires, demonstrations, strikes, and a workers movement reaching

the highest level in all of Latin America between 1890-1918, (Rock, 1977;

Godio, 1979; del Olmo, 1999).

These events during the last years

of the 19th century and the first decade of the 20th century are the context

for Argentinas criminological boom. On the other hand, the development of the

Italian Positivist School was considered fundamental in correcting problems

such as crime and became most significant in Argentina following the 1885 Rome

Congress on Criminal Anthropology (del Olmo, 1999).

Its highest expression was the

creation in 1907 of the Institute of Criminology at the National Penitentiary

of Buenos Aires. It was considered the first in the world to scientifically study

prisoners with the aim of arriving at an adequate treatment regimen for their

readaptation. Lombrosos teachings were closely followed (Blarduni, 1976).

Francisco de Veyga and José

Ingenieros were given the responsibility of developing and applying the Italian

Positivist School to Argentinas criminal policy. Their official positions

enabled them to integrate theory and practice. Francisco de Veyga, a forensic

doctor, created, in 1897, the first course of Criminal Anthropology and

Criminal Sociology in the Faculty of Medicine of the University of Buenos

Aires. While he was director of the Police Service, he nominated his pupil

Ingenieros as clinical chief of the Police Service.

De Veyga is recognized for

pioneering clinical criminology in Argentina, but José Ingenieros consolidated

the direct study of criminals. In 1890, de Veyga started the Forensic

Psychiatry Clinic at the same prison, appointing his pupil as director. In

1902, he changed its name to the Psychiatric and Criminological Clinic, where Ingenieros

created, the following year, an Experimental Psychology Laboratory as the first

attempt to apply psychology to the study of criminals in Argentina. In 1907,

Ingenieros became director of the new Institute of Criminology of the National

Penitentiary of Buenos Aires, where he remained until 1914, when he resigned.

He developed a questionnaire for observing and examining criminals, called the Psychological

and Medical Bulletin, which continued to be applied by those who followed

him. The National Penitentiary of Buenos Aires, and within it the Institute,

became so well known that it was visited by internationally prominent figures.

Aside from their official posts,

both doctors engaged in intense intellectual activity. In 1902, de Veyga

founded the Archives of Psychiatry and Criminology, appointing

Ingenieros as director. The statement of mission in the inaugural issue of 1902

mentioned that the journal had as its aim to spread the scientific study of

abnormal men especially criminals and the insane as well as the conditions

of the psychological environment that affect them. It was soon the best-known

Argentinian journal internationally, with frequent contributions from

specialists from various countries. When the Institute of Criminology was created

in 1907, the Archives became its official journal.

Criminología is considered to be the first book on clinical

criminology published in the world (Pinatel and Bouzat, 1974). In it,

Ingenieros developed the Scientific Program applied to the study of criminals

at the Institute. He divided criminology into three areas: (a) criminal

etiology, i.e. the causes of crime; (b)

clinical criminology, the study of the multiplicity of criminal acts to

establish the degree of danger; and (c) criminal therapy, determining

the social and individual measures needed to assure societys defense by the

correction of the criminal.

Although Ingenieros Criminology

is based on the fundamental premises of the Italian Positivist School, he aired

his disagreements with Lombroso and Ferri in a paper entitled The

classification of criminals, which he presented in 1905 at the Fifth

International Psychology Congress in Rome (Fig. 7). For him, criminal

morphology was similar to that of all degenerates; the difference between

criminals and the rest, he believed, could be discovered in the field of

psychopathology. In this regard, Ingenieros wrote the following: The

development of a new orientation in the study of criminals to complement the

Italian Positivist School, according to scientific criteria gathered in the

clinic and the laboratory, is imminent. The study of anthropological

abnormalities is destined to give way to psychological abnormalities

(Ingenieros, 1957b). Thus, Ingenieros stressed the relationship between crime

and insanity. To him, crime was the product of abnormal psychic functioning,

which explains why he has been considered the founder of the psychopathological

school of Criminology.

3.4. El hombre mediocre

Ingenieros was probably the most

important positivist in the Argentinian tradition. Yet so eclectic he was, that

his ideas frequently exceed the positivist discourse. As Lorena Betta (2005)

has it, "his thought receives contributions from a most diverse

variegation of cultural and philosophical movements. Influences come from

positivist and evolutionist roots, include the modernist, romantic, and

spiritualist lineages, and continue until reformist marxism and the

revolutionary wing. In this combination play a part thinkers such as Darwin,

Spencer, Sarmiento, Lenin, Trotsky, Lunacharsky, Ruben Darío, José Martí, Rodó,

Vasconcelos, Emerson, Barbusse and Nietzsche." He rejected traditional

religious formulations of problems as falsely posited. The true metaphysical

questions arise out of, yet beyond, the sciences. But because they concern

matters of which we have no present experience, they are more adequate to

generate hypotheses rather than dogma. Ingenieros was gripped by evolution and

saw the possibility of human perfectibility. It brought special problems to his

views. Emerenciano Ramírez Villasanti (2001) points that in

order to formulate his convictions in a framework of evolutionary materialism,

Ingenieros developed deterministic interpretations of human and natural

affairs. This poses special conundrums in matters of ontology and ethics, as

determinism results incompatible with any aspiration of intentional

perfectioning. This makes Ingenieros the moralist to collide with Ingenieros

the scientist, an inflection point that was specially addressed by his follower

Gregorio Bermann (1894-1972) in his 1918 thesis probing determinism and free

will. Ingenieros yet went ahead by pointing that ideals themselves are

hypotheses for the improvement of human nature.

In El hombre mediocre (Ingenieros,

1913b, 1913c, 2001), a work that rivaled José Enrique Rodó's Ariel in its impact upon Latin American

youth, Ingenieros saw ideal values as being the production of a creative élite,

which is typically thwarted in its moral ambitions by mediocre human beings

(Smart, 1999).

Mediocres

are massified

persons unable of forming or striving for an ideal, who thus panic about

originality, rejecting creation and bustle to espouse apathy and stability. For

reformists, then, professors were "mediocre men". Their social

function was providing stillness rather than progress. In contrast,

"superior" people distinguish the needs of the time and use their

talents to fulfill them. For them, ideals are motivating factors for individual

and social progress. Anyone so doing is "young" by definition, and

definitionally young men are the ultimate formulators of ideals and those who

will bring about a better future. Yet narrowing this broad notion of youngness,

Ingenieros argued that human perfectibility is a privilege of the biological

youth: only physically young men strive for perfection and take action toward

it. Reformists of course identified themselves as Ingenieros's "superior

men" and wished that the university was the place in which male students

would be educated in the traits of "the new man" not by the old

professors, certainly.

Biased readings notwithstanding,

the pages of El hombre mediocre his work par excellence and a most

important work in Social Psychology, taught even today at many Universities

worldwide as a masterpiece of morality, social philosophy and literature

constitute the severest and most eloquent critique against all those who, in

the name of vulgarity and mediocrity, are against the progress of the

individual in ones eternal fight to procure an ideal. Through an accuracy of

opinions and communicative accent of sincerity with neither ties nor

prejudices, the book deserves without a doubt to be considered of exceptional

value, offering in its pages an inappreciable treasure of a live and lasting

education.

3.5. Philosophical naturalism and evolutionary

positivism

Positivism was a philosophical

stance comprising scientific, deterministic, psychological, evolutionary,

biological and sociological topics. Positivists admired Darwin and prized Comte

and Spencer as their philosophical heroes. Preference for one or the other gave

rise to evolutionary or social positivist tendencies, respectively. Positivists

rejected a priori and intuitive methodologies and praised science as

providing the most reliable knowledge about humans and the universe, and tried

to produce syntheses of scientific findings in which they elucidated the nature

of physical, biological, psychological and social phenomena (Rabossi, 2003).

The number of Latin American

positivist thinkers is large, and their extraction and importance diverse; it

is generally agreed that Ingenieros, along with Venezuelan-Chilean Andrés Bello

(1781-1865) and Cuban Enrique José Varona (1849-1933) were among the most

original and influential. Originality in this case means variation around

positivist nuclear tenets. For example Ingenieros' contribution, as dissected

by Oscar Terán (1986, 2000), shows its originality in its superposition of

ideological periods, passing from anarchizing socialism to latinoamericanist

anti-imperialism (e.g., Ingenieros 1922b) through Spencerian positivism and the

mounting moralist tendencies crystallized in El hombre mediocre. Other important positivists in Latin America,

all revolving around the positivist notional hard core with their own style of

variation, were Gabino Barreda (1820-1881) and Luis Villoro (b. 1922) of México

and Carlos Vaz Verreira (1871-1958) of Uruguay (Gracia and Millán, 1995).

The list of original pieces produced

during the positivist period by Latin American philosophers includes

Ingenieross Psicología Genética (1911a) and later Psicología

Biológica (1913a). Through it, Ingenieros helped to introduce Auguste

Comtes positivism into Argentina; he called it Genetic Psychology (Corsini,

2002). Evolutionary positivism gained particular popularity among several

scientists at the University of Buenos Aires, including Ramos-Mejía,

palaeontologist Florentino Ameghino (1853-1911), sociologist Carlos Octavio Bunge

(1875-1918, Mario Bunge's uncle) who called for biology-like social evolution

to curb revolution, and Ingenieros, who, although they did not formally found a

school (Martí, 1998), did have considerable influence.

In Genetic Psychology,

Ingenieros begins as a committed evolutionist, but admits the need for

improvement, feeling that inductivism neglects the speculative aspect of

science. As a solution, in his book Proposiciones relativas al porvenir de

la Filosofía (Propositions about the Future of Philosophy) a

program to define philosophy along scientific positivist lines he proposes an

experiental metaphysics that could generate future scientific hypotheses

(Ingenieros, 1918; 1960).

Proposiciones is one of his most original works; in it, Ingenieros exposes

a version of positivism that made metaphysics possible. He maintains that it is

possible to recognize, in all form of experience, an experiential remainder (residuo

experiencial) that is not unknowable, although it does not have a

transcendental character.

Ingenieros also found evolutionary

ethics unable to account for human ideals and in his Hacia una moral sin

dogmas an attempt to ground ethics on idealism and evolutionary

theory he pursues an idealism that can only be justified in evolutionary

terms (Ingenieros, 1917; 1961). But An ideal is a gesture of the spirit to

perfection. Thus, rather than the familiar methods of material stimulation to

boost up the development of productive forces, in Las fuerzas morales he regarded moral incentives as the motive

force of social progress.

4. Principios de Psicología Biológica

4.1. Publication history

According to the introductory note

of the definitive sixth edition (Ingenieros, 1946), the work initially appeared

in 1910 in separate chapters in the publication Argentina Médica. The

chapter Biological Psychology appeared in Archivos in 1910

(Ingenieros, 1910b), when Ingenieros was 33 years old (Fig. 13). In 1911, all

of the chapters were published under the title Psicología Genética (Ingenieros, 1911a) and the subtitle Historia natural de las funciones

psíquicas in a special volume of Archivos de Psiquiatría y Criminología (No. 10, January-April 1911).

Fig. 13. Ingenieros at age 33 in 1910, the year the first

article on Biological Psychology appeared in Archivos (from Editorial,

1925a). He then attended the American Scientific International Congress as

President of both the Argentina Medical Association and the Society of

Psychology of Buenos Aires.

The first publication of Ingenieross Psychology in

independent book form happened in 1913 (Fig. 14, left) under the title Principios

de Psicología Biologica, as part of the series Biblioteca

Científico-Filosófica published by Daniel Jorro, Editor, Calle de la Paz,

23, Madrid (Ingenieros, 1913a) and printed by Luis Faure, Alonso Cano, 15,

Madrid.

A French translation of the

Spanish edition, prepared by R. Delpeuch, was published in 1914 in Paris (Fig.

14, center) by Librairie Félix Alcan, Boulevard Saint-Germain, 108, as

part of their series Bibliothèque de Philosophie Contemporaine (Ingenieros,

1914a), printed by Imprimerie Paul Brodard, Coulommiers. Th. Ribot soon wrote

an analysis of that work in La Revue Philosophique (Paris) (No. 7,

1914), which in a Spanish translation was published in La Semana Médica in

November 1914 in Buenos Aires (Ingenieros, 1916a).

Fig. 14. Frontispiece of the three European editions of

the Principles of Biological Psychology: the 1913 Spanish edition (left),

the 1914 French edition (center), and the 1922 German edition (right).

An authorized German translation

(Fig. 14, right) of the first Spanish edition, prepared by Julius

Reinking, with an Introduction by Nobel Laureate and notable figure of German

science and letters Professor Wilhelm Ostwald of Leipzig, was published in 1922

by Verlag von Felix Meiner, Leipzig (Ingenieros, 1922a), printed by Druck der

Spamerschen Buchdruckerei. Ostwald, a chemist and philosopher, had been awarded

the Nobel Prize for Chemistry in 1909.

Between 1913 and 1916, five

successive editions of the work were published in Buenos Aires. The revised

fifth edition (corregido por el autor,

con un apéndice, y aligerado, al mismo tiempo, de notas que son innecesarias

para lectores ya versados en las disciplinas filosóficas modernas i.e., corrected by the author, plus an

appendix; and unburdened from notes uncalled for readers already knowledgeable

in modern philosophical disciplines), appeared in 1916 under the shortened

title Principios de Psicología (Ingenieros, 1916a) from Talleres Gráficos de L. J.

Rosso y Cía, Belgrano 475, Buenos Aires (Fig. 15, left). It carried the

following subtitles that specified its fundamental criteria: I Fundamentos

biológicos de esta ciencia natural. II Su posición en la filosofía

científica. III La formación natural de las funciones psíquicas. IV El método genético (I Biological fundamentals of this natural science.

II Its position in scientific philosophy. III The natural formation of psychic functions.

IV The genetic method).

Fig. 15. Frontispiece of the last two Buenos Aires

editions under the shortened title Principios de Psicología: (left) the

fifth edition of 1916; (right) a later (1946) printing of the sixth and

definitive edition of 1919.

The sixth and definitive edition (nuevamente revisada por el autor, y

su texto puede considerarse definitivo) was published in 1919 in Buenos Aires

by L. J. Rosso. A modern printing by Editorial Losada, S.A., Buenos Aires

followed (Ingenieros, 1946), printed on 20 December 1946 at Artes Gráficas

Bartolomé U. Chiesino, Ameghino 838, Avellaneda, Buenos Aires (Fig. 15, right).

The definitive edition of Principios

de Psicología forms volume 9 of the Complete Works (Obras Completas)

of José Ingenieros, published in 24 volumes between 1930 and 1940 by Ediciones L. J. Rosso, Buenos Aires (Ingenieros,

1937); volume 9 of Obras Completas published

in 20 volumes in 1957 by Elmer Editor, Córdoba 2240, Buenos Aires, and printed

by Talleres Gráficos de la Técnica Impresora S.A.C.I., Córdoba 2240, Buenos

Aires (Ingenieros, 1957a); and included in volume III of the 8-volume set of Obras

Completas published in 1962

by Ediciones Mar Océano, Buenos Aires (Ingenieros, 1962).

To our knowledge, the work was

never translated into English. Perhaps 21st century science will value the Principios in a manner disconnected from the

political disposition of its author. One may speculate on the reasons for the neglect, be as they may mixed

religious, political and social. Even as an insider, Ingenieros remained an

outsider. He was loved by liberal intellectuals and students, but hated by the

establishment, even when he became part of it, as University of Buenos Aires

Professor, Police Laboratory Director, and so forth.

4.2. Prefatory remarks by Ingenieros

Ingenieros (1913a) begins his

3-page Preface with the definition that Biological Psychology studies the

natural formation of psychic functions in the evolution of living species,

in the evolution of human societies, and in the evolution of individuals; and

continues: Its more general results allow the establishment of a System of

Genetic Psychology, comprised of Comparative (Phylogenetic), Social

(Sociogenetic), and Individual (Ontogenetic) Psychology.

Continuing in the Preface, he

iterates: We conceive Psychology as a Natural Science that conforms to the

more general hypotheses of Scientific Philosophy; we treat its problems with

the help of the criteria of deterministic evolutionism. The genetic method in

Psychology applied in different fashions by Spencer, Romanes, Ardigó, Ribot,

Baldwin, Sergi and several others that we cite furnish the elements which,

placed in harmony with the data of auxiliary sciences, allow already to

establish its more general laws and to coordinate them in one system

In

considering Psychology as a Biological Science, we do not restrict the domain;

the genetic method, applied to the study of the Philosophical and Social

Disciplines, permits the reconstruction of the formation of Logic, of Morality,

of Aesthetics, of Sociology, of Law, etc. and to study them as Natural Sciences

reposed on Psychology.

And he concludes the Preface in

the following words: In formulating the essential principles of our academic

teachings, we propose to contribute to the establishment of Biological

Psychology as a Natural Science and conforming to the genetic method, and to

make it enter into the general system of Scientific Philosophy, which

continually elaborates and rectifies its hypotheses following the natural

rhythm of experience.

4.3. Structure and subject matter

All editions contain the original

Preface that is dated 1910. The first edition (Ingenieros, 1913a, 1914a, 1922a)

contains the Preface and ten Chapters, denoted by Latin numbers I through X.

The fifth edition (Ingenieros,

1916a) contains an Advertencia de la 5a Edición dated 1916, the

original Preface from 1910, the ten Chapters of the previous editions, and an

Appendix that consists of a 34-page essay titled Los fundamentos de la

psicología biológica, previously published in the May 1915 issue of Revista

de Filosofía.

The sixth edition (Ingenieros,

1946) contains an Advertencia de la 6a

Edición dated 1919, and the original 1910 Preface, while the ten chapters are

now re-structured in an Introduction plus

nine Chapters denoted by Latin numbers I through IX.

All editions conclude with a

10-page section titled Conclusiones sintéticas (Synthetic conclusions),

which is a compilation of all of the Conclusions sections that mark each

Chapters ending.

The titles of the ten Chapters of

the first five Spanish editions, published between 1913 and 1916 (as well as

those of the 1914 French translation and the 1922 German translation) are the following:

I: Scientific Philosophy. II: The natural formation of living matter. III:

Biological energetics and psychic functions. IV: Psychic functions in the

evolution of species. V: Psychic functions in the evolution of societies. VI:

Psychic functions in the evolution of individuals. VII: The natural formation

of conscious personality. VIII: The natural formation of the function of

thought. IX: Psychological methods. X: Biological Psychology.

The contents of the definitive

sixth Spanish edition (published in 1919 and reprinted in 1937, 1946, 1957 and

1962) are structured as follows: Introduction: Science and Philosophy. I: The

natural formation of living matter. II: The natural formation of psychic

functions. III: Psychic functions in the evolution of species. IV: Psychic

functions in the evolution of societies. V: Psychic functions in the evolution

of individuals. VI: The natural formation of conscious personality. VII:

Intellectualism and Rationalism. VIII: The genetic method. IX: Concept and

definition of Psychology.

One notes the following

modifications in the sixth definitive edition (Ingenieros 1946): Chapter I of

the previous editions now becomes Introduction: Science and Philosophy;

Chapters II-VII are re-numbered as Chapters I-VI, retaining their exact titles,

with the exception of Chapter III, which instead is named Chapter II: The

natural formation of psychic functions; Chapters VIII-X are renamed and become,

accordingly, Chapters VII: Intellectualism and Rationalism, VIII: The genetic

method; IX: Concept and definition of Psychology.

4.4. Summary of the text of Principios de Psicología

Biológica

We

have provided a complete English translation to our knowledge, the first ever

presented of Conclusiones Sintéticas (Triarhou and del Cerro, 2006),

based on the first Spanish edition of the work (Ingenieros, 1911a; Ingenieros,

1913a). It is reproduced below. Each one of the ten chapters is headed by its

original title in the book. The three diagrams that formed part of the original

publication are included as Figures 16, 17 and 18; a selection of authors to

whom Ingenieros makes reference are mentioned at the end of each chapter.

I. Scientific Philosophy. The knowledge of reality is a natural result of the

empirical experience, always relative and limited. Imagination allows to exceed

its data, through the formulation of hypotheses that depart from it and which

seek to be ratified by it. A science, at each moment of its formation,

expresses the laws of its actual experience and the hypotheses of its possible

experience. Experience, a fundamental of the sciences, was also the basis for

all philosophy. There is no science without hypothesis, there is no philosophy

without experience. Their natural formation is progressive. The particular pace

of the sciences and of philosophies may at times disagree because of the

disparity of methods used to treat their respective problems; but, in general,

the formation of both follows the pace of experience and is effected as a

function of the social environment.

Scientific philosophy is a system

of hypotheses founded on the most general laws demonstrated by particular

sciences to explain the problems that exceed the current or the possible

experience. It is a system in continuous formation. It has methods, but has no

dogmas. It corrects itself with the pace of varying experience. Elaborated by

people evolving in an environs that evolves, it represents an unstable

equilibrium between growing experience and rectified hypotheses. The most

general results of the sciences converge to demonstrate three fundamental

hypotheses: the unity of the real, its incessant evolution, and the determinism

of its manifestations. These must apply to resolve the metaphysical problems:

the origin of matter, of life and of thought.

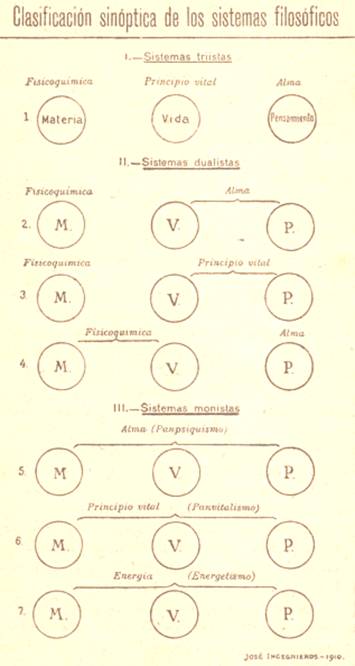

Fig. 16. Synoptic classification of philosophical

systems, dated 1910. From Principios (Ingenieros, 1913a).

All science is characterized by

the impersonality of its methods, which are the natural results of experience;

all philosophy is characterized by the systematic unity of its hypotheses.

Intuitionism finds that metaphysical problems are inaccessible to the means of

scientific methods; criticism finds that reality is heteromorphous and escapes

all unitary or systematic explanation. Scientific philosophy tends, on the

other hand, to be a system of hypotheses founded on experience and proposes to

explain the unknown on the basis of the known: it is a metaphysics of

experience.

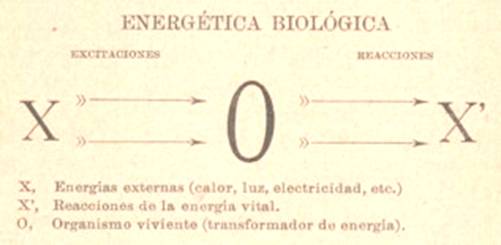

Fig. 17. Diagram of biological energetics according to

Ingenieros (1913a).

Among the writers and scientists

Ingenieros cites are Ardigó, Ribot, W. James, H. Spencer, Bacon, Spinoza, Kant,

Newton, Fichte, Lamarck, H. F. Osborn, Metchnikoff, W. Ostwald, as well as

Plato, Aristotle and Eucleid.

II. The natural formation of

living matter. The natural formation

of living matter can be explained by means of a unitary hypothesis,

evolutionary and genetic.

On the basis of the most general

assumptions of modern energetics on the constitution of matter, its diverse

states or forms may be conceived as an uninterrupted series of energy

condensations, derived from each other through the transformation of their

atomic-molecular structure (morphogenesis) and characterized by the acquisition

of properties (physiogenesis) that allow to differentiate them. The states of

matter actually known are stakes of a series whose terms we largely ignore, and

which could be discovered with time.

Fig.

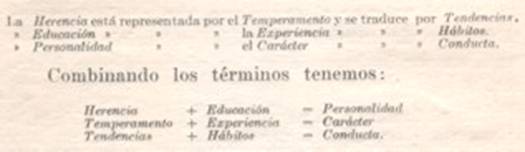

18. Components of behavior and their combinations and yields,

according to Ingenieros (1913a).

The states of matter, evolutionary

in a constant course, constitute the «species» of matter, whose structure and

properties «evolve» over periods of time that cannot be evaluated in relation

to the human life-span; that is why their transformations escape physical

chemistry, and science can occupy itself with the states that present to our

actual experience as if their structure and properties were invariable.

The genetic study of living beings

reveals that all «varieties» of protoplasms constitute a single

physico-chemical «species», in the structure of which dominates the colloidal

state, and among the functions of which assimilation is essential; either of

these is already apparent in certain states of non-living matter, tending at

the same time to bring it closer to living matter, in the course of the

«evolution of the species of matter». Its «variations» determine innumerable

«equilibrium forms» represented by biological species, varying at the same time

their «functions of adaptation».

The artificial formation of living

matter is improbable, because one ignores the «phylogeny» of the species of

matter. On the contrary, its natural formation can be considered as a permanent

result of the «variability» of the «species» of matter more immediate to it by

its structure and their functions, although it escapes our actual experience

because of its extension in time.

Authors mentioned by Ingenieros

include J. Moleschott, Claude Bernard, Pasteur, Virchow, Bergson, Ostwald, as

well as Heracleitus, Aristotle, Pythagoras, Epicurus, Galen and Paracelsus.

III. Biological energetics and

psychic functions.

Biological functions are the result of incessant energy permutations in